The Day After Project Funding Alternatives for Increasing Civil Expenditure

- Ido Lan and Yoni Ben Bassat

- 1 בדצמ׳ 2023

- זמן קריאה 27 דקות

עודכן: 13 באוג׳ 2025

Ido Lan and Yoni Ben Bassat

Chief editor: Amit Ben-Tzur

Hebrew editing: Daphna Lev

English translation: Carly Golodets

Design: Adi Ramot

February 2024

The project was written in response to the revealed weaknesses of the government and public services during the October 7 War.

How can we fund the rehabilitation of civil services in Israel? In this paper we present various policy alternatives for funding reinvestment in civil services in Israel, while implementing the Bank of Israel investment plan to close the productivity gap between Israel and the OECD. The alternatives were examined using a simple macroeconomic model that examines the effect of different funding mixes on the main economic variables.

The different alternatives test different scenarios of increased civil expenditure. In the Bank of Israel investment plan alternative, we propose to implement the plan published by the bank, which involves increasing the country’s budget by 3.25% of GDP. In the other scenarios we propose to increase expenditure by 5.1% or 9.8% of GDP to raise public expenditure or civil public expenditure to the OECD average. All of the alternatives we examine can be funded without significantly increasing the deficit, by raising the tax burden to levels considered acceptable in many developed countries.

The results of the model indicate that the low public expenditure in Israel is a policy choice and that rehabilitation of civil services is possible.

Abstract

Background

The civil failure: the October 7 war revealed the weaknesses of the civil services in Israel.

The civil services have suffered for years from under-budgeting, and civil public expenditure in Israel is among the lowest in the OECD.

Under-budgeting also has a significant impact on labor productivity and the standard of living of Israel’s citizens.

This paper proposes several policy alternatives to fund the expansion and improvement of civil services, taking into consideration the economic impact of the war and its associated public expenditure.

Alternatives for increasing expenditure

The Bank of Israel investment plans – to encourage investment in physical and human capital to boost labor productivity. the Bank of Israel’s recent investment plans necessitate an annual supplement of approximately 3.2% of GDP to the country’s budget.

The expansionary policy alternatives described in this paper propose to significantly increase civil expenditure by approximately 5.1% or 9.8% of GDP. This increase will also enable implementation of investments to increase labor productivity and the standard of living of Israel’s citizens as well as rehabilitate the civil services.

90 expansionary policy – raising civil expenditure by approximately 5.1% of GDP to equalize the OECD average (approximately 90 billion ILS in 2022 terms).

171 expansionary policy – raising civil expenditure by approximately 9.8% of GDP to equalize the OECD average (approximately 171 billion ILS in 2022 terms).

Alternatives for funding the increased expenditure

All the alternatives in this paper were built to represent responsible fiscal policy that maintains the debt-to-GDP ratio in Israel below the OECD average.

The tax burden in Israel is low with respect to the OECD countries, and very low with respect to the comparison countries. Thus, it is clear that government revenue can be significantly increased by increasing taxes.

We are examining two funding possibilities to increase expenditure: full funding though taxes (tax expansionary policy alternative), and a mix of funding through debt (tax and debt expansionary policy alternative).

Raising taxes is not popular, particularly during a war. The low debt-to-GDP ratio in Israel allows temporary funding of the expenditure increase and rehabilitation of the civil services through debt, while the raise in taxes will be postponed until 2028.

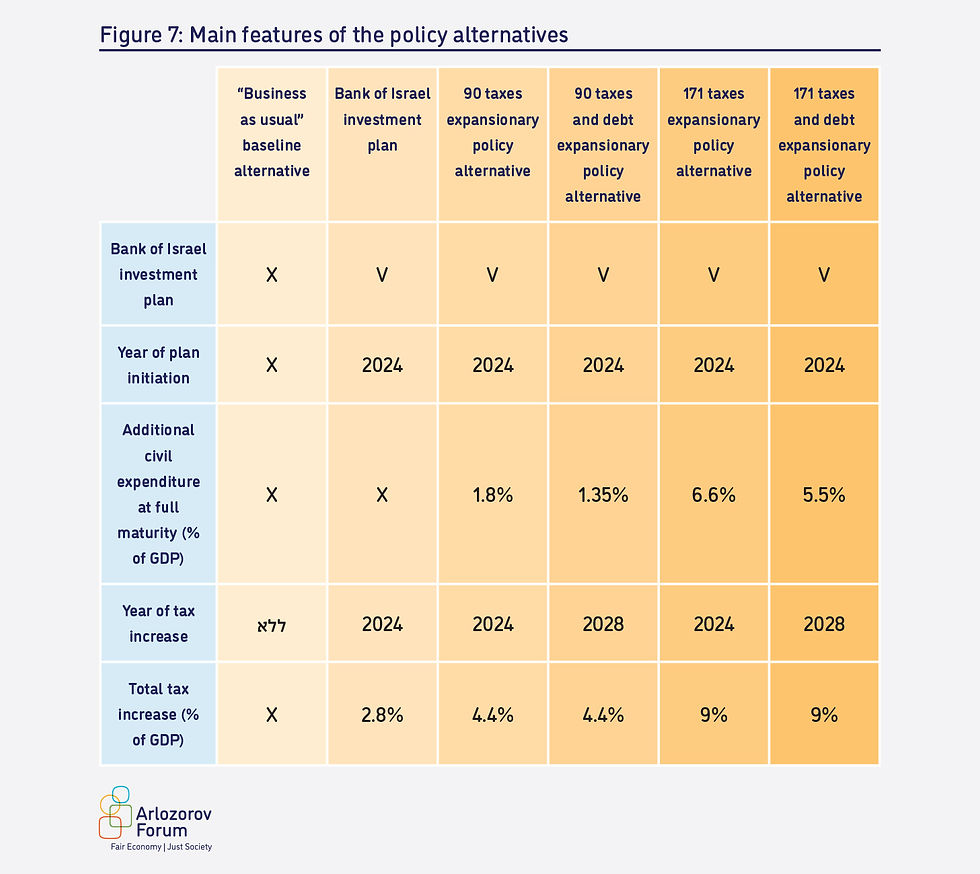

Six policy alternatives

Baseline alternative: continuing current trends (“business as usual”), taking into consideration the economic impact of the war. This alternative will be funded by increasing the deficit in the short term and reducing civil services in the medium term, similar to the plan proposed by the government.

Bank of Israel investment plan alternative: implementing the Bank of Israel investment plan to the effect of 3.2% of GDP. This alternative will be funded by raising taxes.

90 tax expansionary policy alternative: increasing civil expenditure by 90 billion ILS. This alternative will be funded by raising taxes.

90 tax and debt expansionary policy alternative: increasing civil expenditure by 90 billion ILS. This alternative will be funded by debt combined with raising taxes from 2028.

171 tax expansionary policy alternative: increasing civil expenditure by 171 billion ILS. This alternative will be funded by raising taxes.

171 tax and debt expansionary policy alternative: increasing civil expenditure by 171 billion ILS. This alternative will be funded by debt combined with raising taxes from 2028.

Analysis of the policy alternatives

We examine all the alternatives using a simple macroeconomic model that tests the effect of the alternatives on the GDP, deficit, public debt, government expenditure and government revenue.

Implementing the Bank of Israel investment plan alternative will lead to a 12% increase in GDP per capita within two decades. In contrast, implementing the expansionary policy alternatives will lead to a 14–18% increase beyond the expected increase in the baseline alterative.

Under the two 90 expansionary policy alternatives, civil expenditure per capita in 2043 will be approximately 30% higher than in the baseline alternative. Under the two 171 expansionary policy alternatives, it will be approximately 50% higher. This increase stems from both the increase in GDP and the increase in percent GDP allocated to civil expenditure.

Summary

The low investment in civil services in Israel is a policy choice rather than a necessary outcome of the security situation.

Rehabilitation of the civil services will require a significant increase in civil expenditure, which must be funded by raising taxes.

The low debt in Israel allows temporary funding by increasing the civil services budget through debt, which may increase the political feasibility of choosing an expansionary policy.

Background: The Civil Failure and the “Day After” Project

The October 7 war emphasized to the entire Israeli public the tremendous importance of strong civil services that provide solutions during both routine times and emergencies. The trend of continued under-budgeting, which has taken place over approximately four decades, particularly since 2003, brought Israel, prior to the war, to a situation in which the civil services were thin and weak. Beyond the security–political failure that led to the outbreak of the war, the inadequate functioning of government ministries and the civil services, during our darkest hour, constitutes a comparatively serious civil failure.

The “Day After” project is an initiative of Arlozorov Forum, in response to the revealed weaknesses of the government and civil services during the October 7 war. Within the framework of this project, we published a series of reviews in different fields, designed to describe the main problems facing the civil services and propose solutions. For example, in the field of healthcare, private health insurance is eroding the universal public healthcare system, impacting health equality and raising the cost of healthcare (Ben Bassat, 2023); in the field of education, there is an acute lack of early childhood educational frameworks (age 0–3), enormous disparities between population sectors, and children’s achievements are relatively low on an international scale (Bar Chaim, 2023); in the field of welfare, understaffing has led to a great file overload on social workers and inequality between strong and weak local authorities (Vaknin Ganel, 2023); and in the labor market, vocational training has been almost completely neglected, impacting labor productivity and economic growth (Weinblum, 2023).

Nevertheless, the project is not designed to describe the dimensions of the failure; rather, it is first and foremost an optimistic project. The crisis we experienced gives us an opportunity to change direction: from neglect and reduction to rehabilitation and rebuilding of the civil services. In the public discourse in Israel, the term “big government” has been used to describe an “inflated” government, with many redundant ministers and ministries. In the reviews of the “Day After” project we use the professional meaning of the term “big government”: a government that employs many nurses, female teachers, female social workers, policewomen and many other public employees, and pays them a suitable salary that attracts the best women and men to the public service. In other words, we propose to choose the policy of a big government, one that is responsible for many essential aspects of the daily lives of its citizens, providing universal, accessible, quality civil services and a dense social safety net. In other words: the basic assumption of the project is that all the problems we have identified can be solved and the civil services can be rehabilitated, but this requires adoption of a different economic policy that puts the civil services in the center.

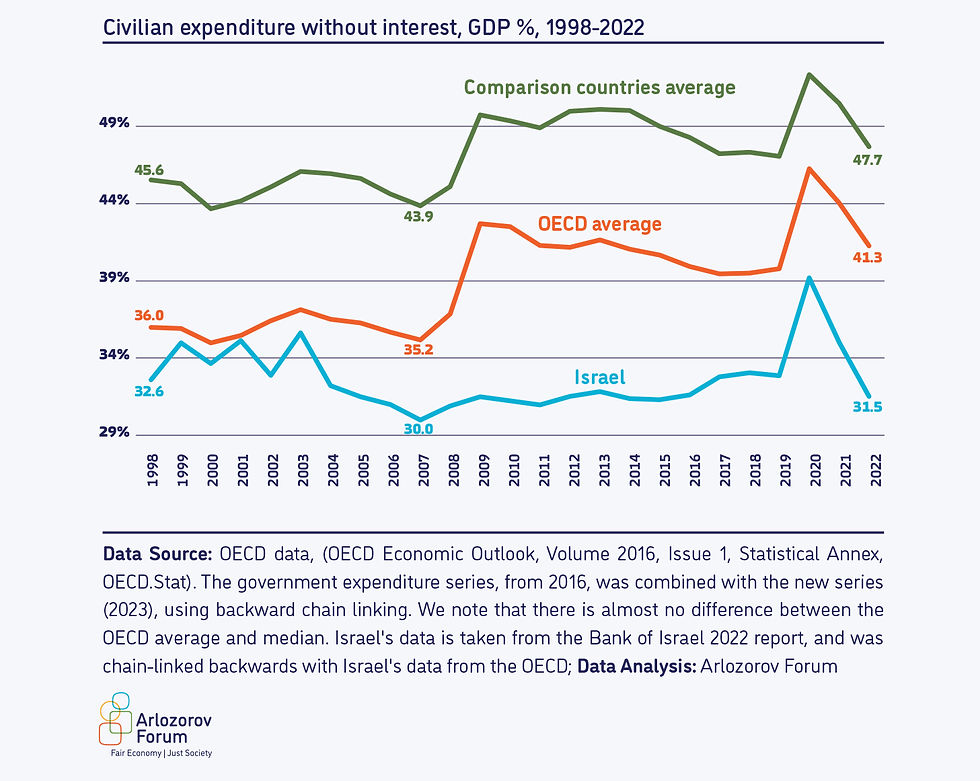

To understand the size of the disparity, Figure 1 compares civil public expenditure in Israel to average expenditure in the OECD and the comparison countries1. In 2022, civil expenditure in Israel was 9.8 GDP percentage points lower than the OECD average and 16.2 percentage points lower than in the comparison countries. Comparison to other developed countries allows us to define the potential range of policy alternatives. In other words, if other countries can maintain a thriving economy and high GDP per capita with such high public civil expenditure, it is reasonable to assume that this is also possible in Israel.

A. The Macroeconomic Impact of the War

The most significant and severe impact of the war is undoubtedly the impact on human life. However, wars also have extensive macroeconomic impacts with repercussions for many years after the battles are over (Zeira, 2021; Stravchinsky and Poleg, 2007).

The immediate impact of the war is expressed by decreased economic activity, mostly due to the evacuation of towns, recruitment to reserve duty, and closing of educational frameworks (Bank of Israel, 2023a; 2023b). According to indices of credit card expenditure, the decrease in economic activity reached a low of approximately 20% in the first two weeks of the war (Bank of Israel, 2023c). In the longer term, the economic impact results mainly from the impact on the entry of workers to Israel, tourism, physical capital, accumulation of human capital and supply chains (Bank of Israel, 2023b). Similarly, beyond its economic impact, the war significantly affects government expenditure and revenue, particularly due to payments to reservists, defense purchases, severance pay and rehabilitation payments (for example, expenditure related to the Tekuma Authority) (Ministry of Finance, 2023).

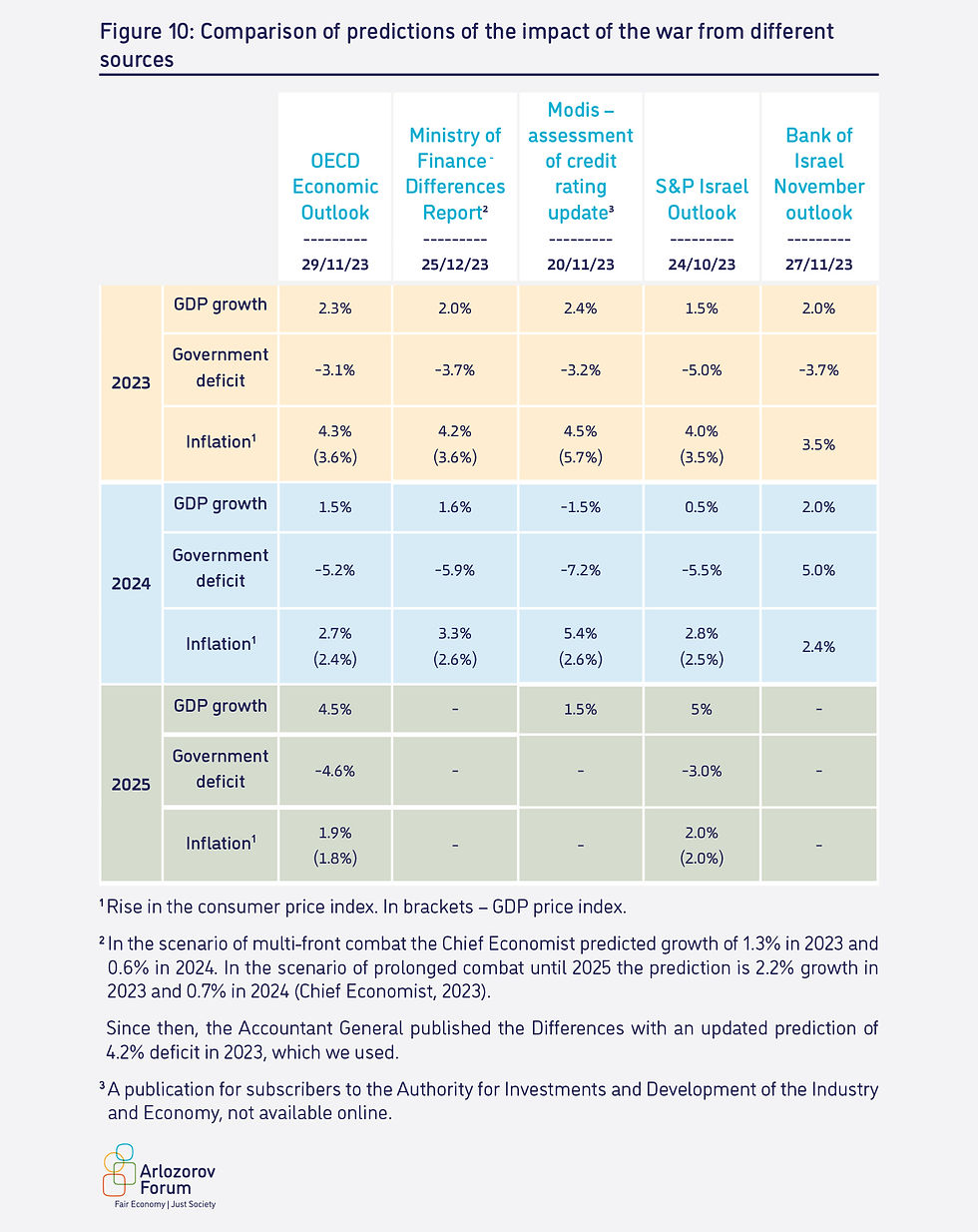

In practice, it was almost impossible to estimate the macroeconomic impact of the war at the time this paper was being written, due to the high level of uncertainty regarding future developments. Different research bodies estimate different levels of damage, where one of the main risk factors for the expansion of the economic impact is expansion of the intense war to additional fronts (Ministry of Finance, 2023; Bank of Israel, 2023d; Chief Economist, 2023; OECD, 2023a; Moody’s, 2023; S&P Global, 2023). The basic assumptions that guided our analysis are based on the OECD estimates (OECD, 2023a)2. The main assumption that underlies our analysis is that in 2026 the Israeli economy will return to its long-term growth path (according to Bank of Israel estimates), but with the fixed addition of 1% of GDP to defense expenditure until 2030.

Nonetheless, even an increase in defense expenditure does not rule out the possibility of increasing the proportion of GDP allocated to civil expenditure. Figure 2 depicts the composition of government expenditure for the period 1981–2022. In the 1980s and 1990s, 16% and 9% of GDP were allocated to defense expenditure, respectively, on average, compared to approximately 5% of GDP in recent years. Nevertheless, although the interest burden was also significantly higher than it is today, civil expenditure stood at 35% of GDP compared to 31% today. In other words, the historical data teach us that increasing the defense expenditure burden does not have to come at the expense of reducing civil expenditure.

B. The Policy Alternatives

The aim of the policy proposed in this paper is rehabilitation of the civil services whose weaknesses were revealed with the outbreak of the October 7 war. Although some of the problems revealed can be solved through better management and preparation of an emergency plan, most of the problems cannot be solved without financial investment. Israel’s economy already finds itself at a 20% disparity with respect to labor productivity, which stems partly from low levels of public investment (Bank of Israel, 2019; Hazan and Tzur, 2019). During the war we saw great enlistment of volunteers and civil society organizations, but in the long term, the provision of basic services to all citizens, without discrimination, throughout the year, can only be maintained if they are funded by the government and public budgets. Therefore, we focus on proposing funding alternatives for increasing civil expenditure.

Analysis of the policy alternatives is based on a simple macroeconomic model that relies on several assumptions external to the model, including the growth trajectory, the effect of taxation and civil expenditure on GDP, and the trajectory of public debt development (see Appendix A for details). The model is based on previous policy papers published by Yesodot Institute (Kollerman, 2020, 2022), where the baseline prediction is compatible with the Bank of Israel baseline prediction (Bank of Israel, 2021a, 2022), combining necessary adaptations due to the war and the changes in macroeconomic indices that occurred since they were published3. In the following alternatives we describe the expected development of the main macroeconomic indices over the next two decades (2023–2043). We emphasize that this is a baseline model that aims to describe the range of policy alternatives, without a dynamic analysis of business cycles.

Alternatives for Increasing Expenditure

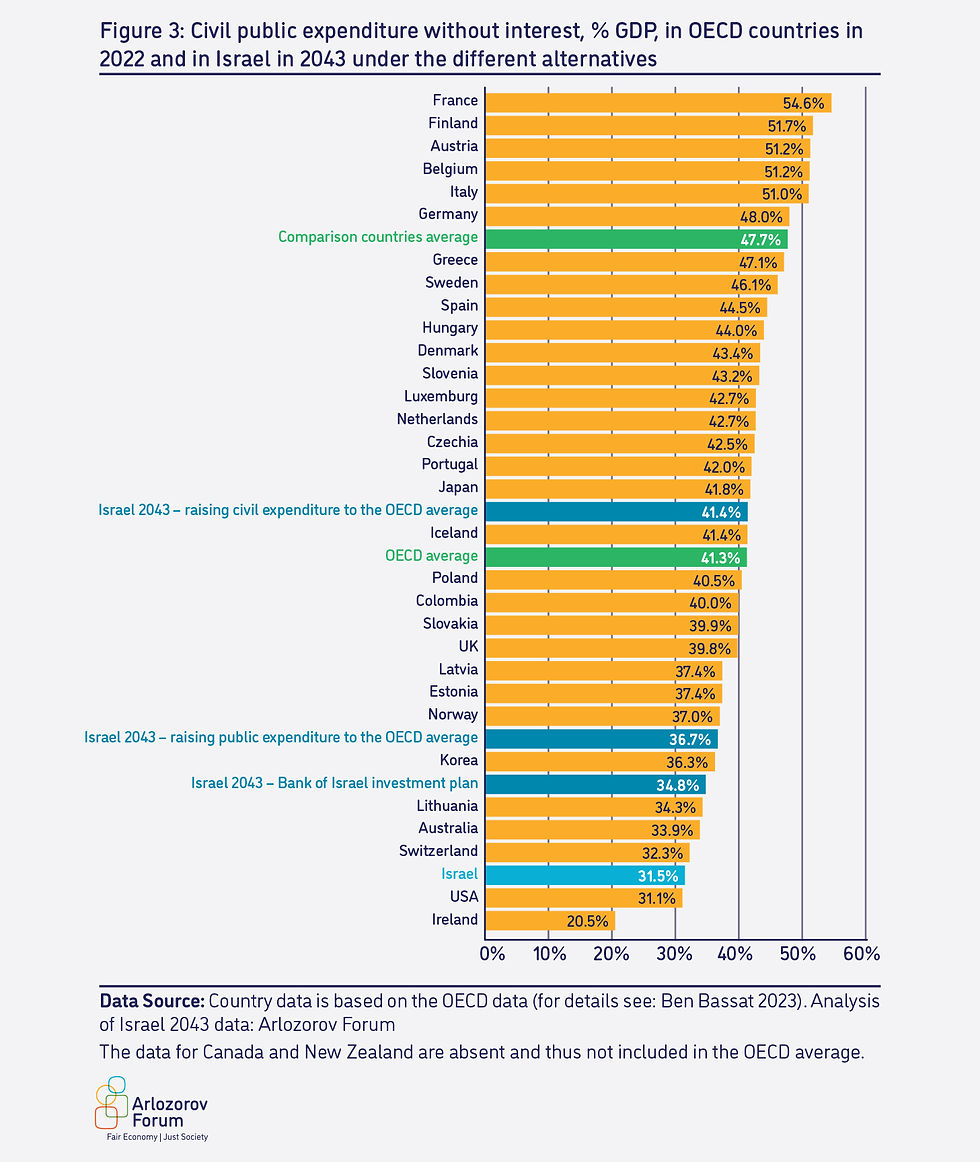

We will now detail three main expenditure alternatives that were used to construct the expenditure scenarios in the policy alternatives: the Bank of Israel investment plan, raising both public and civil expenditure to the OECD average (Figure 3). We emphasize that all the policy alternatives described here maintain the level of civil expenditure in Israel below that of most of the OECD countries. In the baseline alternative, civil public expenditure in Israel is lower than that of all the OECD countries except for the USA and Ireland.

We note that in contrast to the Bank of Israel alternative (Bank of Israel 2021a, 2022) and those proposed by Kollerman (2022), this paper does not include the cutbacks in current government expenditure as a funding alternative for increasing government expenditure. To ensure full implementation of all the proposed steps in the “Day After” project, there is indeed a need to streamline existing services. Nevertheless, since the aim of the expenditure scenarios is to test the feasibility of a “big government”, cutbacks to existing expenditure undermine this aim. Likewise, similar expenditure in the past was often based on reducing defense expenditure as a funding channel, but this channel does not appear realistic in the coming years due to the war. In all the policy alternatives analyzed in this paper we even assume that the defense budget will increase in the coming decade.

The Bank of Israel investment plan

A series of publications by the Bank of Israel (2019, 2021a, 2022) details the public investment and reforms required to increase labor productivity in Israel and narrow the productivity gap in relation to other developed countries. The bank warns that the skill level of workers in Israel, as measured by PISA and PIACC surveys, is low, and the disparities in the skill levels of different workers are greater than in other developed countries. Similarly, according the bank’s publications, the public capital stock in Israel is low, as expressed by the low quality of transport and communications infrastructure, which affects labor productivity. Among the steps recommended by the bank: raising public expenditure per student to the OECD average and massive investment in infrastructure, particularly public transport.

In total, the cost of the policy steps proposed by the Bank of Israel is approximately 3.2% of GDP annually; this is supposed to contribute approximately 1% annual growth at full maturation. Despite the repeated publication of the plan over the years, it has not been adopted by Israel’s governments. This plan, and the assumptions it carries, underlie the different alternatives that we present to increase public expenditure.

b. Raising public expenditure to the OECD average: the 90 billion plan

Since defense expenditure burdens civil expenditure in Israel, the main expenditure scenario includes raising public expenditure in Israel to the OECD average. In other words, in this scenario we intend to raise the total expenditure (including defense expenditure4) to average OECD expenditure. Thus, beyond the steps detailed in the Bank of Israel investment plan, this plan includes increasing public expenditure by a further 1.8% of GDP before interest (total increase of approximately 5.1% of GDP), which together with the expenditure included in the investment plan add up to approximately 90 billion ILS in 2022 terms.

In this paper we will call the additional expenditure included in the Bank of Israel plan “civil investment” and every additional expenditure that is not included in the Bank of Israel plan we will call “civil expenditure” to emphasize that the yield on this expenditure is lower5.

C. Raising civil expenditure to the OECD average – the 171 billion plan

In the broadest expenditure plan we propose to increase public expenditure so that total civil expenditure in Israel is equal to average civil expenditure in the OECD. Thus, beyond the expenditure detailed in the abovementioned expenditure scenarios, this plan includes additional civil expenditure of approximately 4.7% of GDP (a total increase of approximately 9.8% of GDP), which together with the previously detailed expenditure constitutes approximately 171 billion ILS in 2022 terms.

Funding Alternatives for Increasing Expenditure

The main component of public revenue in Israel is tax revenue, while the remaining revenue is divided between property revenue, sales, interest, public money transfer (such as university tuition fees) and inter-governmental transfers (such as defense aid from the USA) (for details see: Bank of Israel, 2023e). In Israel, over 80% of government revenue is tax revenue. Therefore, for simplicity’s sake, we assume that the other sources of government revenue remain fixed at their current level (in % of GDP), and in the different revenue scenarios we assume an increase in the tax burden6.

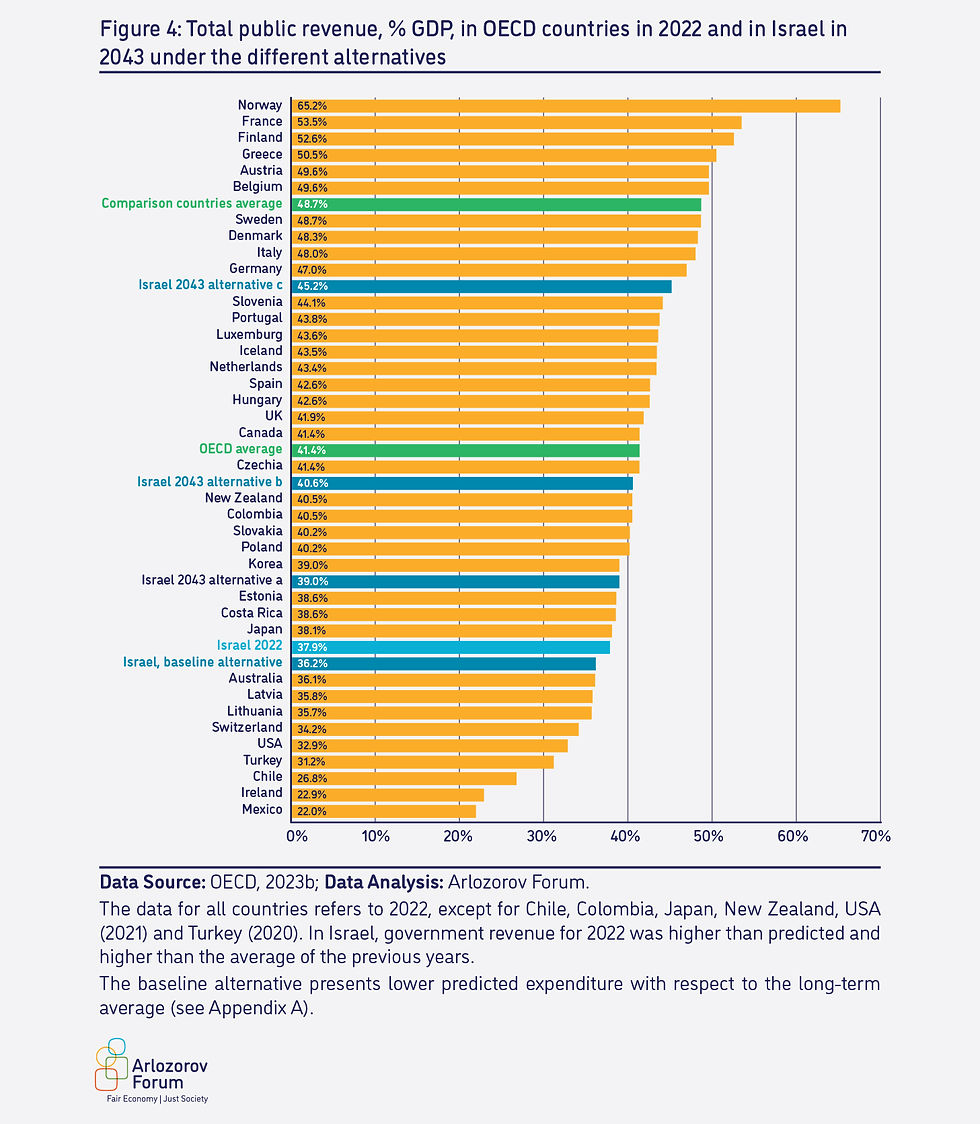

In contrast to what is often thought, public revenue in Israel is low in comparison to other developed countries (Figure 4) and to past revenue in Israel (Figure 5). Thus, in 2022, public revenue in Israel stood at approximately 37.9% of GDP, in contrast to the average of the OECD (41.4%) and the comparison countries (48.7%). In comparison to the past, public revenue in Israel has stood at 36% of GDP on average in recent years7, in comparison to approximately 43% during 1995–2000 and approximately 57% on average in the 1980s. In other words, public revenue in Israel has decreased significantly in recent decades (see also: the Chief Economist, 20228).

As mentioned, in this paper we assume that the expenditure increase will be based on a rise in the tax burden, but we do not detail which types of tax must be raised; rather, we indicate the total expenditure required from taxes. We note that various proposals have been put forward over the years to change the tax rate, impose new taxes or cancel various exemptions (e.g., Ofek-Shani, 2020; Gabai and Sarel, 2018; Hoffman-Dishon and Swirski, 2020; Trachtenburg, 2011; Trachtengurg and Popliker, 2020; Swirski, Spivak and Yona, 2012; Filc, Swirski and Hoffman-Dishon, 2023; Shaanan, 2015; Sheva, 2022). The policy aims underlying the various proposals that were put forward are diverse, from a pure increase in government revenue, through fixing various distortions, increasing economic growth, to minimizing inequality. In other words, the increase in government revenue proposed in this paper can be made possible through various tools, where each set of possibilities has different effects on incentive mechanisms, economic growth and inequality, which require careful consideration.

Furthermore, one of the components that may help increase rate of taxation from GDP is the global initiative to implement a global minimum tax rate of 15% on the profits of large, multinational companies. Although company tax in Israel is 23%, many multinational companies enjoy various exemptions within the framework of the law to encourage capital investment, and their actual tax liability is significantly lower than 15%. Thus, if this global initiative is realized and Israel amends the law accordingly, government revenue from taxes is expected to increase (Bank of Israel, 2022)9.

Raising taxes by approximately 2.75% of GDP (approximately 48 billion in 2022 terms)

This scenario is designed to support increased government expenditure by 3.25% of GDP for the Bank of Israel investment plan. In accordance with the model results described in the next section, this tax increase is enough to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at a similar level to that of the baseline alternative.

b. Raising taxes by approximately 4.4% of GDP (approximately 77 billion in 2022 terms)

This scenario raises the tax burden in Israel by 4.4% of GDP, bringing total government revenue from GDP close to the OECD average. In accordance with the model results described in the next section, this tax increase is enough to finance increased expenditure of 90 billion, and in parallel, stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at a level similar to that of the baseline alternative.

c. Raising taxes by approximately 9% of GDP (approximately 158 billion in 2022 terms)

This scenario significantly raises the tax burden in Israel by approximately 9% of GDP, constituting an increase of approximately 30% in the tax burden. We note that in this scenario the government revenue and tax burden in Israel will be higher than the OECD average, but low with respect to the comparison countries. In accordance with the model results described in the next section, this tax increase is enough to fund increased expenditure of 171 billion, and in parallel, stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at a level similar to that of the baseline alternative.

Deficit and the Debt-to-GDP Ratio

It is commonly assumed that the main restriction to increasing government expenditure without a corresponding increase in revenue is to increase the debt-to-GDP ratio. Increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio leads to an increase in interest expenditure, leading to a possible increase in the risk premium on Israeli bonds (Bank of Israel, 2021a) and a direct impact on the GDP growth rate (De Soyres, Kawai and Wang, 2022)10. Nonetheless, we note that when expenditure is increased for economically beneficial purposes, that is, purposes that contribute to economic growth, it also reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio by increasing GDP (the denominator). Therefore, various proposals have been put forward over the years to exclude investments that encourage growth from the calculation of the normal deficit (e.g., Bank of Israel, 2022).

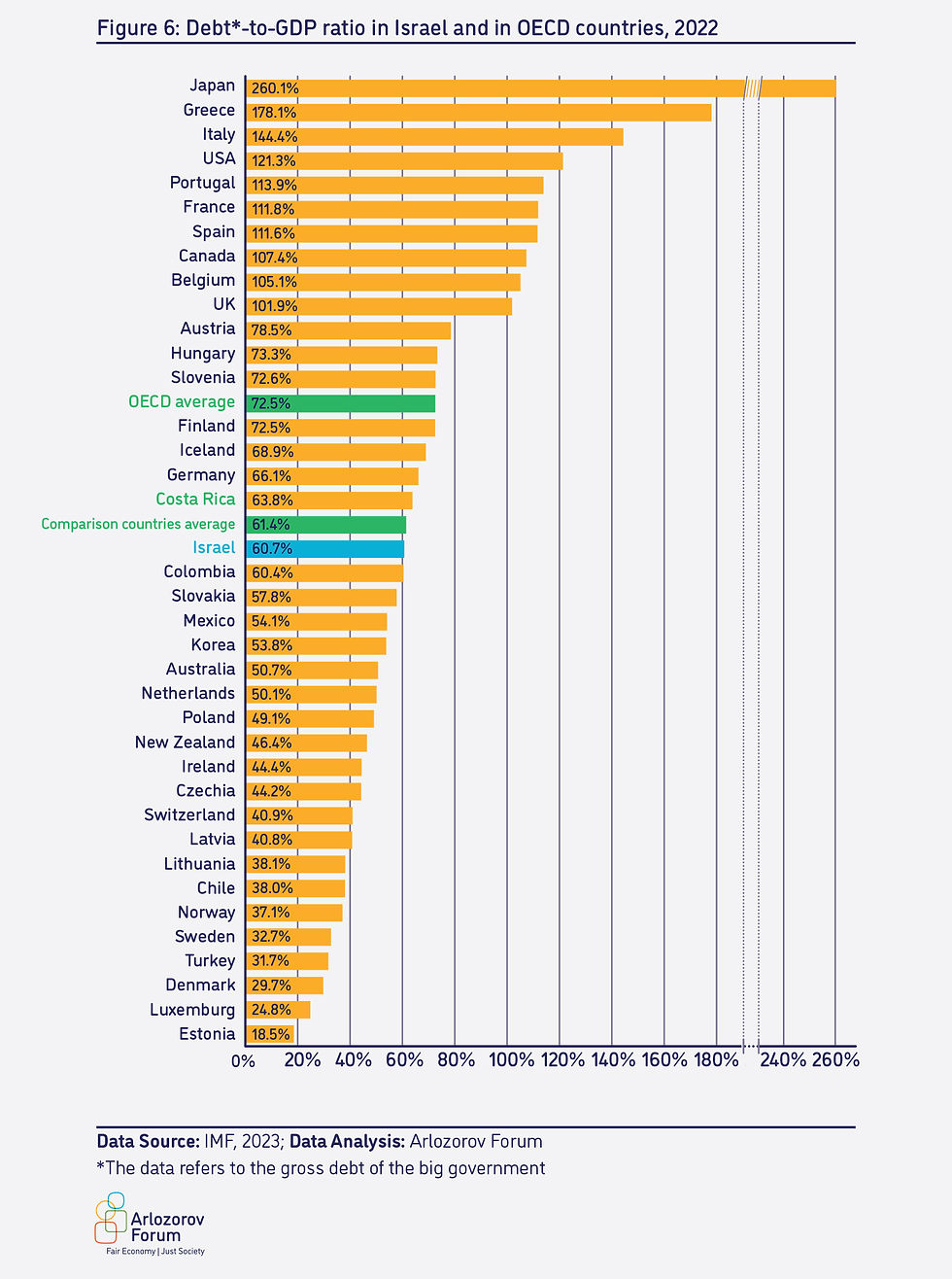

The literature does not indicate any threshold level above which the debt-to-GDP ratio is deemed too high (Pescatori and Heimberger, 2023; Sandri and Simon, 2014), and in some developed countries, such as the USA, Japan and France, the public deficit exceeds 100% of GDP. However, economists recommend that countries maintain the debt-to-GDP ratio at a reasonable level; one of the reasons for this is to maintain a “fiscal space” that allows an increase in the deficit during a crisis (Bank of Israel, 2021b, box F1). Although there is no clear, agreed level, we chose to formulate the policy alternatives such that the debt-to-GDP ratio does not exceed the average OECD ratio at the end of the test period (2043).

Figure 6 presents the debt-to-GDP ratio in Israel and other developed countries. As of 2022, the debt-to-GDP ratio in Israel stood at 60%, approximately 10 GDP percentage points lower than the OECD average. This relatively low debt-to-GDP ratio allows the government to absorb at least some of the costs of the war without a change in revenue or cutbacks in other expenses; thus, a moderate increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio is not expected to have significant negative consequences (see also: Filc, Swirski and Hoffman-Dishon, 2023).

c. Analysis of the Policy Alternatives

Presenting the Alternatives

We will now present six policy alternatives and their analysis according to the model. Beyond the baseline alternative, which describes the continuation of current trends of government revenue and expenditure (“business as usual”), we test three alternatives for increasing government expenditure as detailed above: the Bank of Israel investment plan, raising public expenditure to the OECD average and raising civil expenditure to the OECD average.

In each of the alternatives, implementation of the Bank of Israel investment plan is gradual and continues until 2031, where the contribution of the plan to growth increases gradually to 1% by 204011. Similarly, both the increase in civil expenditure and the rise in taxation rate are spread over several years.

In order to raise the political feasibility of the alternatives, which demand significant taxation, we propose two additional policy alternatives. In these alternatives, initiation of the tax increase required to fund the plan is postponed until 2028, necessitating an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio and reduction in the total increase in civil expenditure. The reason for postponing the tax increase is to allow the Israeli public to recover from the war before additional taxes are imposed, and to increase support for the plan, since the required tax increase will be implemented after the public experiences the beginning of the positive effects of the plan and enjoys the economic growth and social welfare generated by it. The main features of the six alternatives are presented in Figure 7.

Comparing the Alternatives According to Model Predictions

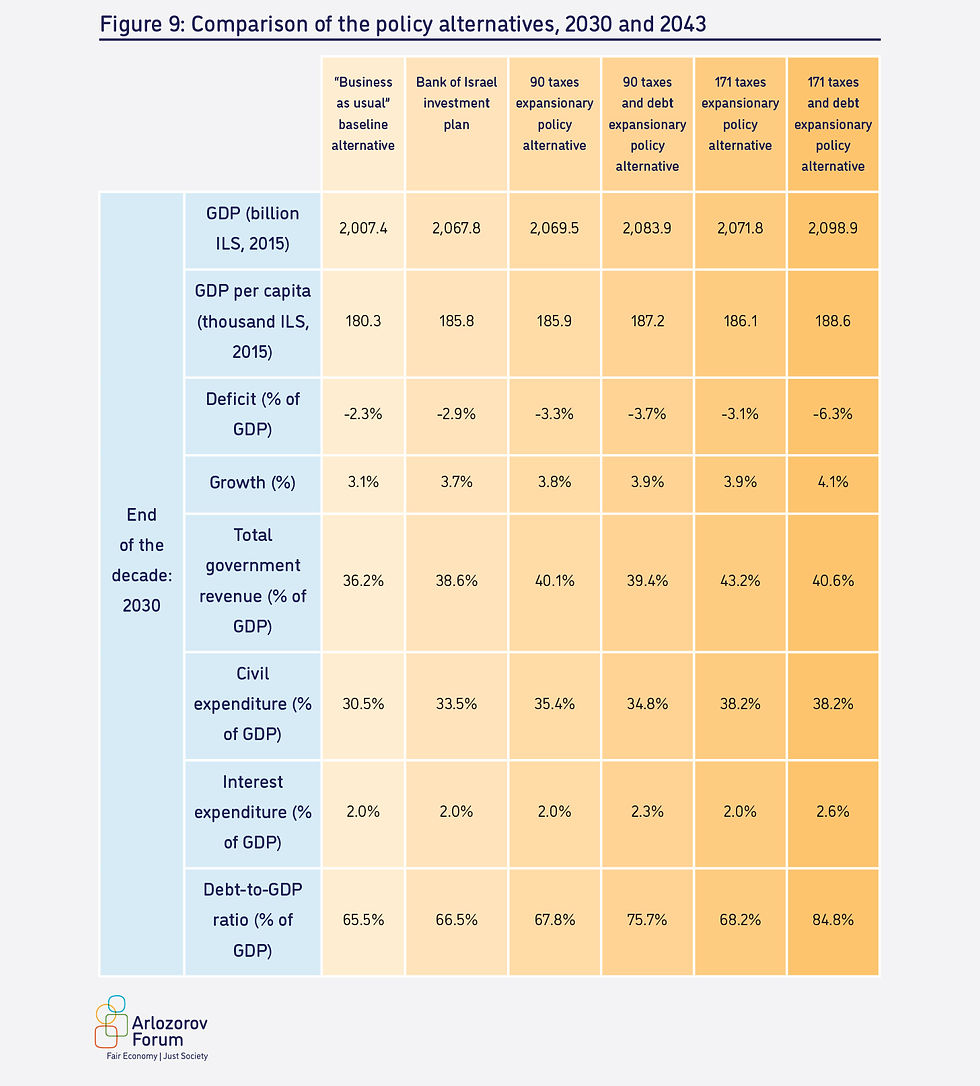

Figure 8 describes how the different policy alternatives affect the development of the main variables in the model: civil expenditure per capita, GDP per capita, the deficit, the debt-to-GDP ratio and the proportion of government revenue and civil expenditure as a percentage of GDP during the years 2022–2043. The main results are described below.

a. Civil expenditure per capita

In each of the policy alternatives, civil expenditure per capita increases at a fixed cost, but while it increases at the (approximate) long-term rate of economic growth in the baseline alternative, in the 90 and 171 expansionary policy alternatives it increases more rapidly, because of both the higher growth rate and allocation of a higher percentage of GDP to civil expenditure. In total, civil expenditure per capita in 2043 will be 23% higher in the Bank of Israel investment plan alternative, approximately 30–32% higher in the 90 expansionary policy alternative and over 50% higher in the 171 expansionary policy alternative.

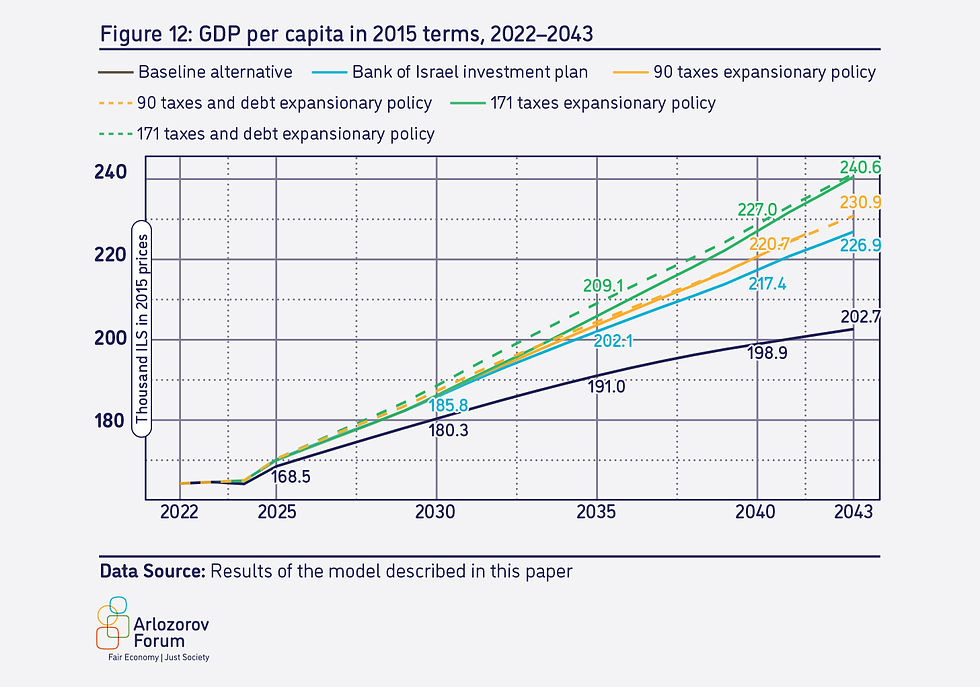

b. GDP per capita

In the baseline alternative, the GDP per capita growth rate is significantly lower due to convergence to a long-term growth rate of 2.3% (representing GDP per capita of only 0.6%)12. In 2043, the difference in GDP per capita between the Bank of Israel investment plan alternatives and the baseline alternative will be 12%. We note that in the alternatives with a more significant increase in expenditure, the increase in GDP per capita is more significant due to the positive multiplier of government expenditure, even given the impact of the taxation rise on growth13. In 2043, GDP per capita in the 171 tax alternative will be approximately 6% higher than in the 171 non-tax alternative and approximately 19% higher than in the baseline alternative.

c. The debt-to-GDP ratio

We can see that all the policy alternatives, except for those based on debt, were planned so that the debt-to-GDP ratio does not exceed 73% at the end of the test period, and is thus lower than the average debt-to-GDP ratio of the OECD (see Figure 6). In the baseline alternative there will be a slight increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio due to the war; subsequently the debt-to-GDP ratio will stabilize at approximately 65%. In the Bank of Israel plan alternative and the 90 and 171 tax expansionary policies, the trajectory of increasing revenue corresponds to the trajectory of increasing expenditure; thus, the debt-to-GDP ratio will stabilize at 68–70%. Conversely, in the 90 and 171 tax and debt alternatives in which the tax increase is postponed to 2028, the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise sharply and then follow a decreasing trajectory for as long as the tax rise is implemented. We note that under the continued described trends, the debt-to-GDP trajectory in the 171 tax and debt alternative will continue its decreasing trend even after 2043 (converging to a low level of 60% for the rest of the century).

Summary of the Comparison of the Alternatives

Figure 9 compares the policy alternatives at two time points: the end of the decade (2030) and the end of the test period (2043). Among all the alternatives, the one with the lowest GDP per capita is the baseline alternative, which does not include the investments required to increase the labor productivity of Israeli workers and raise it to the OECD average. In contrast, the difference between the other alternatives, which differ in their level of civil expenditure, is small in terms of GDP per capita. In this way, the difference between the different alternatives lies, among other things, in the policy decision with respect to the extent and quality of the civil services provided by the government, which will also affect the private/civil funding mix. Thus, a high level of civil public expenditure will also lead to lower private expenditure, for example, in the fields of health and education, and provide a broader safety net for families and households dealing with various difficulties.

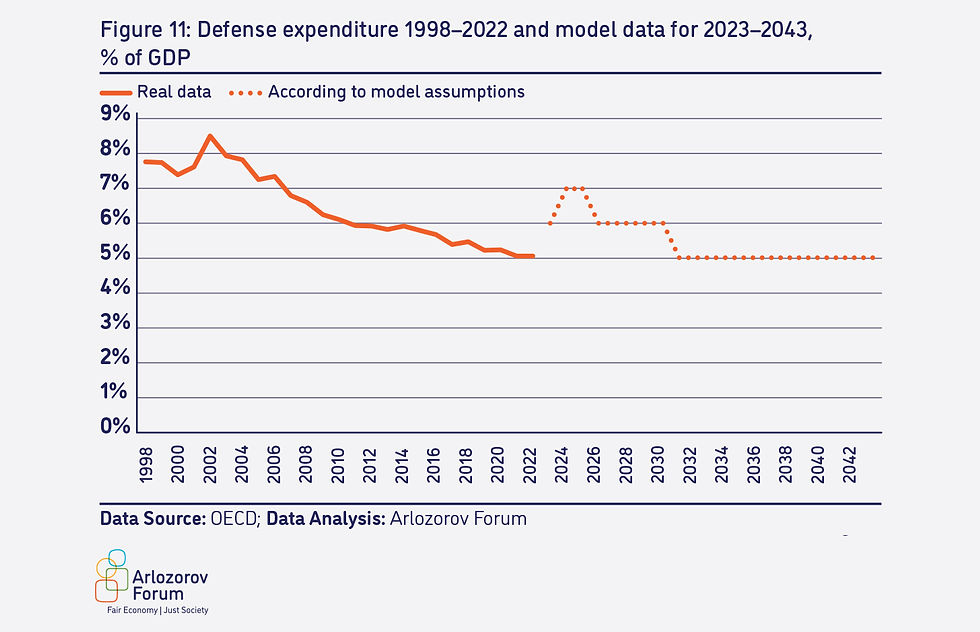

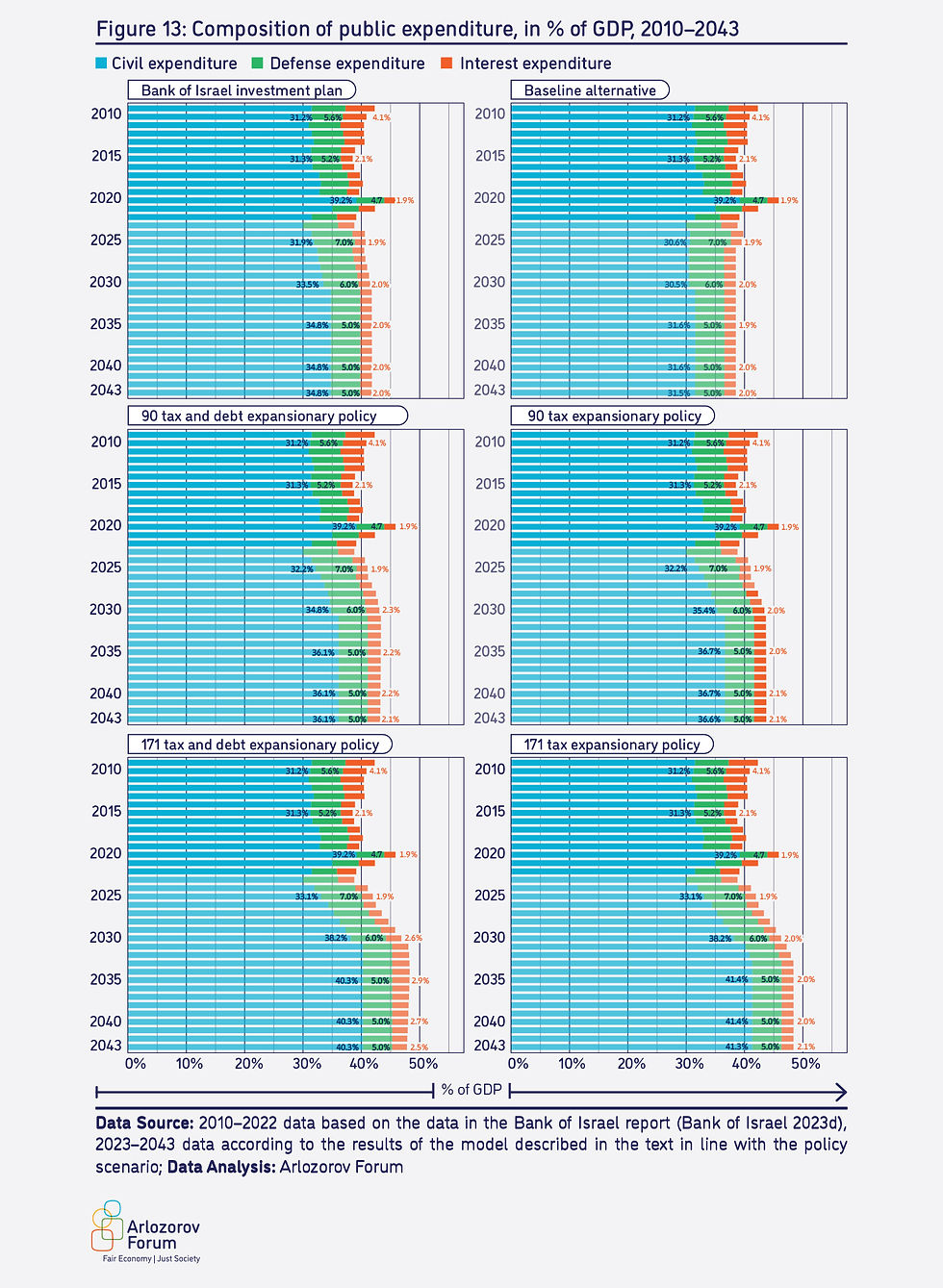

The defense expenditure burden is very significant in Israel, expressed by an expenditure rate that exceeds the GDP, and to a lesser extent, an interest burden due to the risk premium. However, the significant proportion of 5–6% of GDP that is allocated to defense expenditure does not rule out the possibility of a high level of civil services and public investment. In fact, government policy in the last decade has been geared towards low public expenditure even when defense expenditure is included, and very low when it is excluded from the calculation. The prediction included in the model with respect to defense expenditure is detailed in Appendix A, while Figure 11 in Appendix B describes the predicted development of defense expenditure as a percentage of GDP in all the alternatives. Figure 13 in Appendix B describes the evolution of public expenditure composition in the different policy scenarios.

Raising the level of taxation to the OECD average facilitates full implementation of the Bank of Israel investment plan together with a significant increase in civil expenditure. This increase will enable rehabilitation of the civil services to be initiated at the end of the war. In contrast, the two 171 expansionary policy alternatives propose an even more significant increase in the taxation rate, above the average OECD rate, but still below the average rate of the comparison countries. This increase will allow a significant increase in the range of services provided by the government to the citizens, where the level of civil expenditure is equal to the OECD average, despite the high defense expenditure burden.

Clearly, a significant increase in the level of taxation will be met with public opposition. Moreover, increasing the level of taxation may also be perceived as lacking legitimacy with respect to the high prices the Israeli public has been forced to pay during this war and the feeling of abandonment that many are experiencing. The 90 and 171 tax and debt alternatives demonstrate that in the short term it is possible to significantly increase expenditure on civil services without increasing taxes; however, this is not sustainable over time, and an increase in taxes becomes necessary further down the road. Similarly, these alternatives are inferior to the tax alternatives since their civil expenditure is ultimately lower and their debt-to-GDP ratio is higher. However, they may have higher political feasibility due to postponement of the tax increase to the end of the decade.

Summary and Conclusions

This paper is part of the “Day After” project, an initiative of Arlozorov Forum in response to the revealed weaknesses of the government and civil services during the October 7 war. The aim of this paper is to determine whether it is possible to significantly expand the budget framework and fund rehabilitation of the civil services while maintaining responsible fiscal policy.

Over the years, Israel’s governments justified the low levels of civil investment and under-budgeting of civil services by the fact that other developed countries do not have to cope with the expenditure associated with maintaining a large standing army. There is a grain of truth in this argument, since the significance of high defense expenditure in Israel is that in comparison with other developed countries, for any level of civil expenditure, Israel must impose taxes at a higher rate. Nonetheless, even given that defense expenditure will increase due to the war, there is no reason to rule out a significant increase in civil expenditure. Moreover, despite defense expenditure, the level of taxation in Israel is lower than in other developed countries. Raising the taxation level to that practiced in other countries will allow a significant increase in civil expenditure (both implementation of the Bank of Israel investment plan and other civil expenses), thus enabling Israel to recover from this long-term civil crisis.

Israel’s low deficit allows temporary funding of the increase in the civil services budget via the deficit; this should increase the political feasibility of choosing an expansionary policy. However, rehabilitation of the civil services will still require a significant increase in government expenditure, which will need to be funded by increasing taxes. The continued under-budgeting of civil services in Israel is not predestined or an automatic result of defense expenditure. Choosing between high taxation and expenditure and low taxation and expenditure is a political decision. Choosing a policy route that allows implementation of the Bank of Israel investment plan should increase labor productivity and significantly improve the quality of life of all of Israel’s residents. Choosing a policy that also continues to increase civil expenditure will of course require a further raise in the tax burden, but will also significantly improve the quality of life for all of Israel’s residents, reduce private expenditure by the public on civil services, strengthen the economy and turn Israel, into a country that is the best it can be for everyone to live in.

Appendices

A: Assumption and Data Sources

Short-term predictions of the impact of the war on GDP, the deficit and government revenue: There is great uncertainty regarding the macroeconomic impact of the war. The baseline alternative uses up-to-date data published by the Ministry of Finance on growth and deficit in 2023, and predictors published by the OECD in December 2023 (OECD 2023a). The OECD predictions assume that the main economic impact will be felt in the last quarter of 2023, and to a lesser extent in the first quarter of 2024, with relatively rapid recovery in 2025. Deterioration of the combat to additional fronts or a more protracted conflict will lead to a more severe, prolonged economic impact. The predictions disseminated by the different agencies are detailed below (Figure 10).

Defense expenditure: In recent years defense expenditure constituted 5% of GDP. In accordance with different estimates in the media we assume that in the mid-term (until 2030) it will rise by approximately 20% to 6% of GDP (Sharoni, 2023). Similarly, we estimate that the war and rehabilitation during 2024–2025 will cost an additional 1% of GDP, thus, the total defense expenditure during these years will be 7% of GDP14. In the baseline alternative, the assumption is that an increase in defense expenditure will come at the cost of social services, rather than at the cost of increasing taxes or the deficit. Similarly, after 2030, we assume that defense expenditure will return to approximately 5% of GDP, where the available public expenditure will be returned to the social services. Figure 11 describes the predicted development.

Growth trajectory: The baseline alternative, which forms the basis for all the other alternatives, assumes that from 2026 the GDP growth rate will converge to the long-term trajectory, as described in the Bank of Israel long-term model (Argov and Tzur, 2019).

Government revenue in the baseline alternative: From 2026 the proportion of government revenue from GDP is set at 36.2%, based on the average of the previous ten years (2012–2022) (Bank of Israel, 2023e).

The deficit in the baseline alternative: From 2026 the government deficit in the baseline alternative is set to 2.3%, for a long-term debt-to-GDP ratio of 70%. This ratio is slightly lower than the rate set in the Bank of Israel baseline alternative (Bank of Israel, 2021a)

Government expenditure in the baseline alternative: Government expenditure in the baseline alternative is consequential (subtraction of the deficit from government revenue).

Inflation: From 2026, the inflation rate in each of the alternatives stands at 2%, representing the middle of the Bank of Israel target range (Yaron, Ribon and Stravchinsky, 2022). Similarly, we assume that the inflation rate is equal to the change in the GDP price index.

The Bank of Israel investment plan: The cost of the investment plan and its contribution to GDP growth was derived from Bank of Israel (2021a). According to the bank’s estimates, the cost of the plan at full maturation is approximately 3.25% of GDP and its contribution to growth is approximately 1% of GDP.

Additional civil expenditure multiplier: We assumed that each percent of additional expenditure on civil expenditure raises the growth rate by 0.15 percentage points within two years, approximately half of the multiplier according to the rates set in the Bank of Israel investment plan. We note that the multiplier value is significantly lower than in previous studies (see: Gechert and Rannenberg, 2018). In other words, this is a conservative assumption.

Taxation multiplier: In line with the Bank of Israel investment plan (Bank of Israel 2021a, footnote 127), we assumed that the addition of 1% of GDP to taxation reduces the growth rate by 0.075 percentage points.

The real interest rate on the deficit: In the model, the assumption underlying the Bank of Israel investment plan is that the real interest rate is 0% (Bank of Israel, 2021a, Figure 31). We assumed that in accordance with the 2012–2023 average of the real yield to maturity of 10-year bonds, the real interest rate is 1%15, similar to the assumption in the 2021 Bank of Israel report (Bank of Israel, 2022).

Rate of the index-linked debt: We assumed that 50% of the debt stock is index-linked, based on the assumption in the 2021 Bank of Israel report (Bank of Israel, 2022), similar to the current debt mix (Ibid). We note that in the model we assumed no fluctuations in exchange rates, thus there is no difference, as far as the model is concerned, between the debt denominated in foreign currency and the debt denominated in local currency.

Response of the risk premium to the debt-to-GDP ratio: In line with the Bank of Israel investment plan (Bank of Israel, 2021a, footnote 130), we assumed that when the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 77% each additional percentage point increases the real yield on the debt by 0.035% (see also Brander and Ribon, 2015).

Response of the GDP to the debt-to-GDP ratio: In line with the Bank of Israel investment plan (Bank of Israel 2021a), we assumed that the debt-to-GDP ratio does not affect the growth rate. This has been found for countries with high revenue or a low debt rate (De Sovres, Kawai and Wang, 2022).

Appendix B: Additional Figures

References

Argov, E. and Tzur, S. (2019). A long-run growth model for Israel. Discussion paper No. 2019.04. Bank of Israel.

Bank of Israel (2019). Research Department Special Report: Raising the standard of living in Israel by increasing labor productivity.

Bank of Israel (2021a). Four recommended pillars of strategic government action to accelerate economic growth and a fiscal framework for financing them.

Bank of Israel (2021b). Bank of Israel Annual Report 2020: Chapter 6 The general government and its financing.

Bank of Israel (2022). Bank of Israel Annual Report 2021: Chapter 6 The general government and its financing.

Bank of Israel (2023a). Special Analysis by the Bank of Israel’s Research Department: The economic cost of absence from work during the Swords of Iron War. 9.11.2023

Bank of Israel (2023b). Research Department Staff Forecast, October 2023.

Bank of Israel (2023c). Special Research Department Analysis: Credit card expenditures as an indicator of economic activity during the Swords of Iron War. 14.11 2023

Bank of Israel (2023d). Research Department Staff Forecast, November 2023.

Bank of Israel (2023e). Bank of Israel Annual Report 2022.

Bank of Israel (2023f). Special Analysis by the Research Department: The impact of the Swords of Iron War on labor inputs in Arab society. 10.12.2023

Bank of Israel (2023g). Bonds and central bank bills (MAKAM): Yields to maturity.

Bar Chaim, E (2023). The Day After Project: Overview of the education system – civil services and government policy. Arlozorov Forum.

Ben Bassat, Y (2023). The Day After Project: Overview of the healthcare system – civil services and government policy. Arlozorov Forum.

Ben Bassat, Y and Ben-Tzur, A (2023). The Day After Project: Macroeconomic overview – civil services and government policy. Arlozorov Forum.

Brander, A and Ribon, S (2015). The effect of fiscal and humanitarian policy in Israel and the global economy on real yields of central bank bills in Israel: A reexamination after a decade. Bank of Israel. [Hebrew]

Chief Economist (2023). GDP loss estimate – Swords of Iron War. The Chief Economist Division in the Ministry of Finance. 25.10.2023. [Hebrew]

Chief Economist (2022). Government revenue report for 2019–2020 and preliminary data for 2021. Division of the Chief Economist in the Ministry of Finance. [Hebrew]

De Soyres, C., Kawai, R. and Wang, M. (2022). Public debt and real GDP: Revisiting the impact. International Monetary Fund.

Filc, S, Swirski, S and Hoffman-Dishon, Y (2023). Financing the war in Gaza: taxation, debt and division of the burden between workers and capital. Adva Center. [Hebrew]

Gabai, Y and Sarel, M (2018). Direct taxation in Israel – characteristics, biases and recommendations for change. Kohelet Forum. [Hebrew]

Gechert, S. and Rannenberg, A. (2018). Which fiscal multipliers are regime‐dependent? A meta‐regression analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(4), 1160–1182.

Hazan, M. and Tsur, S. (2019). Why is labor productivity in Israel so low? Available at SSRN 3456565.

Heimberger, P. (2023). Do higher public debt levels reduce economic growth? Journal of Economic Surveys, 37(4), 1061–1089.

IMF (2023). World Economic Outlook – Navigating global divergences. October 2023. International Monetary Fund.

Kollerman, M (2020). The expansion plan: What budget policy should the government implement to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis optimally? Yesodot Institute. [Hebrew]

Kollerman, M (2022). A budget for economic growth: What budget policy should the government implement to achieve inclusive growth? Yesodot Institute. [Hebrew]

Moody’s (2023). Government of Israel – A1 review for downgrade. Moody’s investor service – issuer in-depth. 20 November 2023.

Minister of Finance (2023). Report on meeting the fiscal limitations for 2024 (“Differences Report”). Presented to the Finance Committee on 25.12.2023. [Hebrew]

OECD (2023a). Israel, in OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2023 Issue 2. OECD Publishing.

OECD (2023b). General government revenue (indicator).

Ofek-Shani, Y (2020). Where does the money come from? The budget sources that Israel can use to take responsibility for its citizens. The Berl Katznelson Foundation. [Hebrew]

Pescatori, M. A., Sandri, M. D. and Simon, J. (2014). Debt and growth: Is there a magic threshold? International Monetary Fund.

S&P Global (2023). Research update: Israel outlook revised to negative on geopolitical risks; ‘AA’ Ratings Affirmed. 24 October 2023.

Shanan, T (2015) Report on the proposed reform to taxation of international corporations in Israel. Tax Justice Network Israel. College of Law and Business. [Hebrew]

Sharoni, Y (2023). Avoid expenses that aren’t related to the war effort” the Bank of Israel governor in a broad hint to Smotrich. Maariv Business. 19.12.2023. [Hebrew]

Sheva, N (2022). Estimate of government revenue from estate tax. Knesset Research and Information Center, Department of Budget Supervision.

Spivak, A, and Yonah, Y (Eds.) (2012). To do things different: A model for a well-ordered society. the social protest 2011–2012. Red Line, Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House.

Stravchinsky, M and Flug, K (2007). Continuing growth and macroeconomic policy in Israel, from the Bank of Israel survey no. 80. [Hebrew]

Swirski, S, Hoffman-Dishon, Y and Swirski, B (2020). Taxation as an engine of equality. Adva Center.

Trachtenburg, M (2011). Report of the Committee for Social Economic Change. [Hebrew]

Trachtenburg, M and Popliker, E (2020). On taxes and wonders: Towards a reform in the tax system. Samuel Neaman Institute. [Hebrew]

Vaknin Ganel, D (2023). The Day After Project: Overview of the welfare system – civil services and government policy. Arlozorov Forum.

Weinblum, S (2023). The Day After Project: Overview of the labor market – civil services and government policy. Arlozorov Forum.

Yaron, A, Ribon, S and Stravchinsky, M (2022) Inflation and inflation targets. In Yaron, A, and Stravchinsky, M (Eds.) Monetary policy in a period of price stability. pp. 5–37. Bank of Israel Publishing. [Hebrew]

Zeira, J (2021). The Israeli economy. Chapters 3–4. Princeton University Press.

תגובות