Artificial Intelligence Systems in the Workplace: A Comparative Perspective on Risks, Opportunities, Regulation, and Social Partners

- Dr. Gali Racabi

- 10 באוג׳ 2025

- זמן קריאה 29 דקות

Dr. Gali Racabi

August 2025

This paper addresses the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the workplace, focusing on risks, opportunities, regulation, and the role of social partners (labor unions and employers’ organizations). The paper presents various scholarly and regulatory approaches to the effects of technology on the labor market, examines AI regulations in various countries, and offers regulatory pathways for Israel.

Through the comparative analysis conducted in this paper, we identified gaps in Israel’s preparedness for the integration of AI in the labor market, compared with other countries, alongside opportunities to develop tailored regulatory responses. Based on our findings, we propose advancing four levels of regulatory measures in Israel:

1. Increasing attention and learning from global experience;

2. Encouraging experimentation with AI regulation in the workplace;

3. Implementing fundamental legislative, doctrinal, and strategic reforms;

4. Investing in infrastructure and programs for integrating workers from socioeconomic peripheries.

The socioeconomic outcomes of integrating AI systems in labor markets depend on the labor market’s institutional and regulatory structure. Preparing properly and narrowing regulatory gaps could help reduce socioeconomic inequality and mitigate the risks inherent in AI systems.

Executive Summary

Introduction

AI systems are being integrated into the labor market in various ways, namely, employee recruitment and selection processes, work performance monitoring, managerial interactions with employees, and more.

The accelerated technological change resulting from the use of AI systems has sparked discourse on regulating these systems and on the role of workers, labor unions, employers, and regulators.

Alongside investment, development, and implementation of AI tools in the workplace, extensive global engagement in identifying risks and leveraging the benefits of these tools has been undertaken.

Research suggests that the effects of AI adoption in the labor market depend on labor market institutions and strategic responses by employers, unions, and regulators; therefore, labor market institutions can be designed to ensure that AI adoption yields positive economic and social outcomes.

Risks in the Development and Implementation of AI Tools in the Labor Market

As with other technological changes, AI tools may replace workers in performing tasks, lead to unequal distribution of profits among various groups of workers, increase inequality between workers and employers, diminish the influence of labor unions, and weaken the labor market’s institutional framework.

A major concern is the replication of existing discrimination against women and minorities into AI tools (direct discrimination), or the emergence of discriminatory outcomes resulting from their use (indirect discrimination). Another significant concern is the violation of employees’ privacy.

Minimal implementation of AI tools in the workplace might also pose systemic and local risks, such as decreased competitiveness compared with other countries, underuse of profitability potential, and missed opportunities to remedy social disparities.

Comparative Review of AI Regulation

United States: Intensifying economic competition with China and Europe pushed the US administration to adopt unconventional measures, such as significant investments in manufacturing infrastructure, public-private partnerships, and the creation of federal regulatory infrastructure for AI.

China: China’s AI policy seeks to strike a balance between promoting advanced technological development and preserving governmental stability.

Germany: Germany faces a significant shortage of technologically skilled workers, creating pressure to grant work visas to skilled immigrants, which raises concerns about inequality. The law requires employers in workplaces with works councils to disclose AI use to these councils and encourages the counsels’ involvement in AI-based processes.

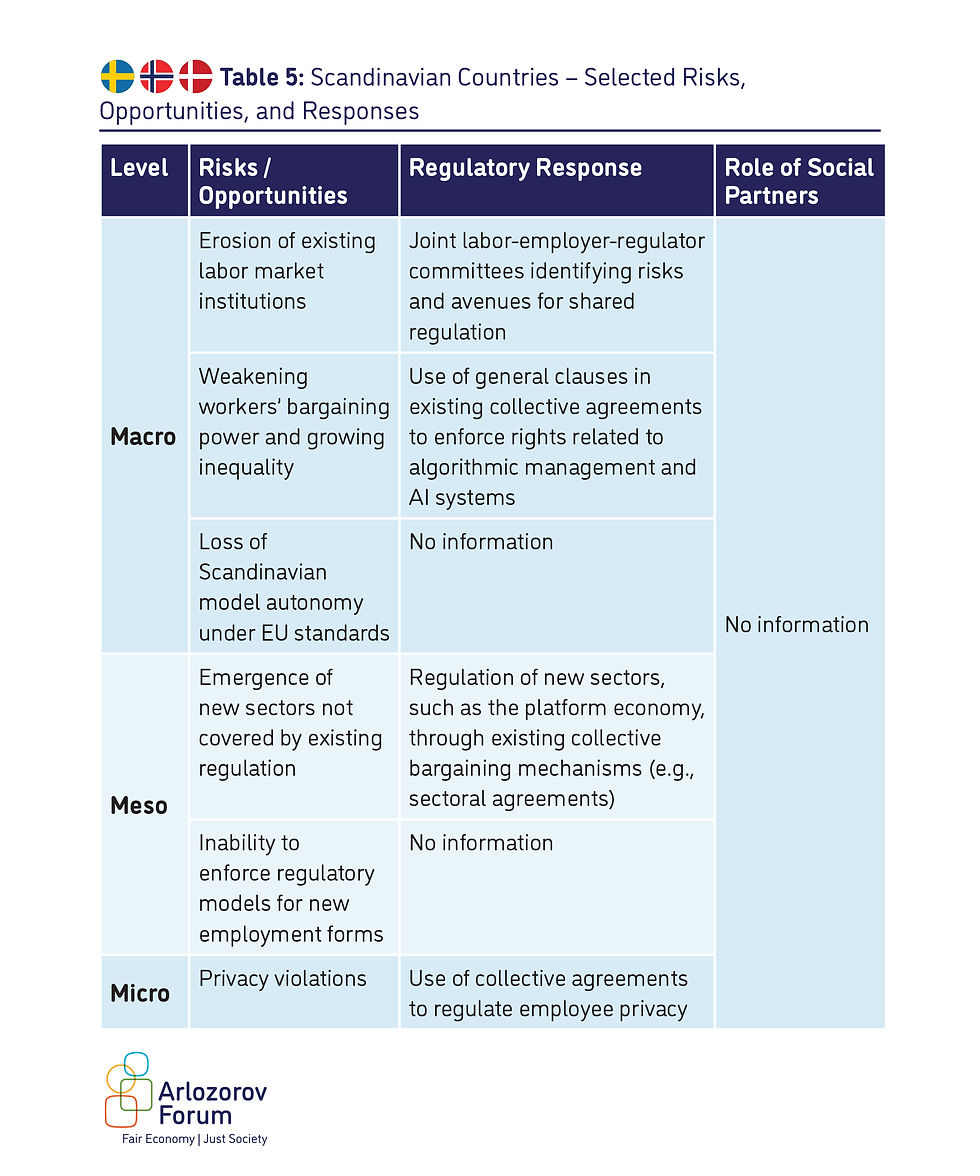

Scandinavian Countries: These countries respond to AI integration in the workplace through joint institutions of the state, employers, and labor unions, under comprehensive regulatory frameworks that govern various rights, while contesting European Union pressures to maintain the Scandinavian model’s independence.

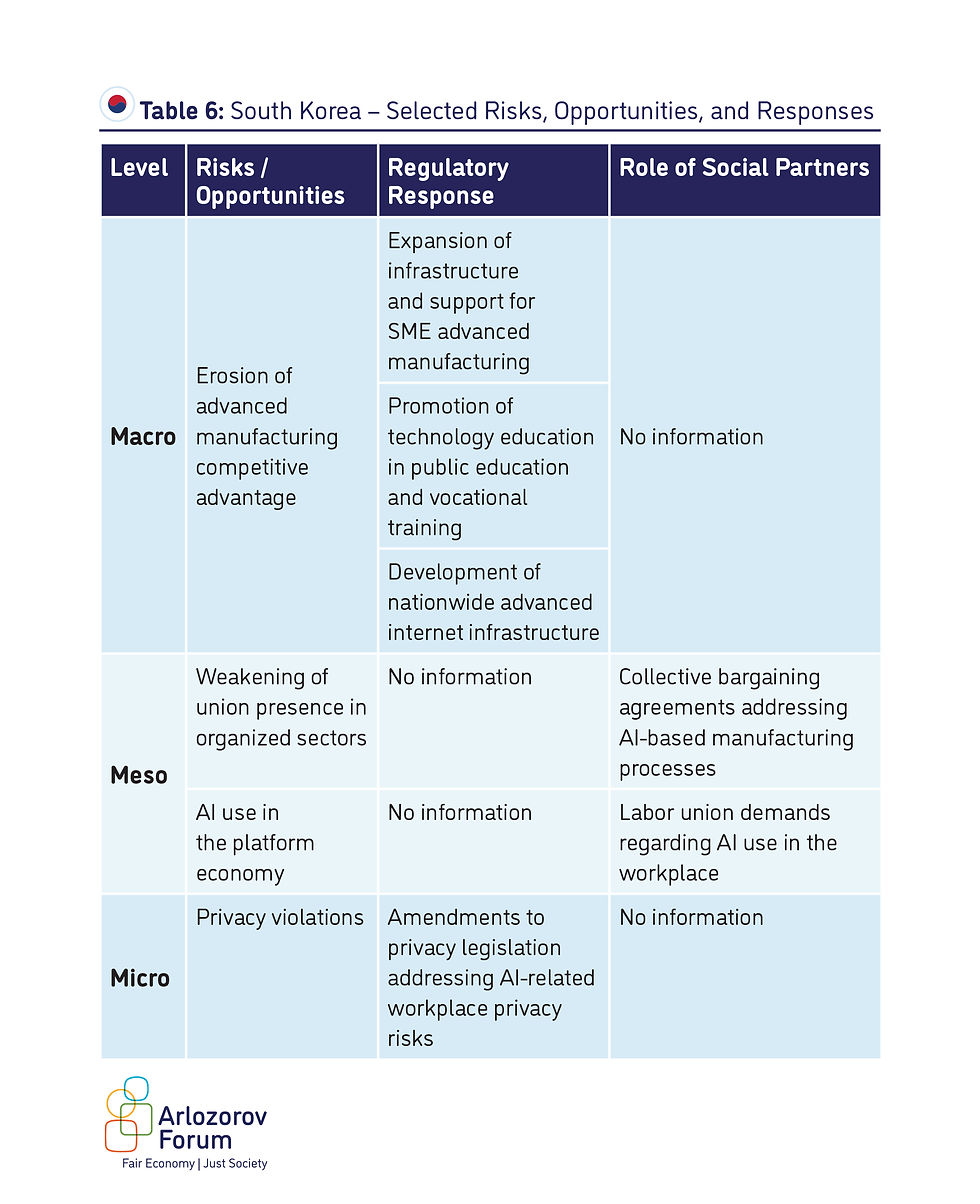

South Korea: The Korean government promotes AI-driven development and production through three regulatory channels, including infrastructure, STEM education, and investment in the technological transformation of small and medium-sized employers.

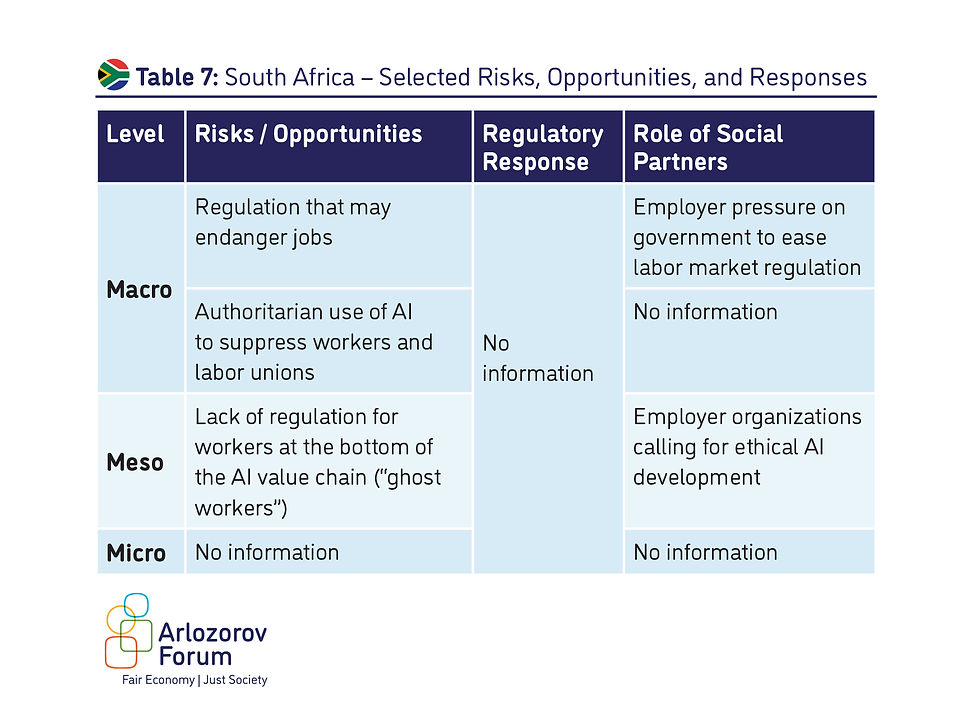

South Africa: In South Africa, two AI-related labor risks exist that are not present in developed countries, namely, risks to workers at the margins of the labor market who participate in the AI value chain and concerns about authoritarian regimes using collected data against workers and labor unions engaged in conflicts with employers and political forces in government.

Israel: Current Situation and Future Proposals

In Israel, national and social partners' preparedness for adopting AI technologies in the workplace is limited. Israel also has less experience in developing labor market regulation for new technologies compared with the countries reviewed (e.g., responses to platform work).

The Israeli Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Innovation issued a policy document on guiding principles of policy, ethics, and regulation, addressing broad questions such as the applicability of existing law and ethical considerations in the development and implementation of AI tools.

Israel has some institutional advantages that enable effective responses to AI systems, including broad labor union coverage and flexibility in the content and scope of agreements among social partners. In addition, Israel maintains extensive protective regulation and legislation, including detailed wage arrangements, broad equal opportunity laws, privacy, and social security laws all regulated by an active labor-focused judicial branch.

On the basis of the analysis we conducted for this paper, we propose advancing four levels of regulatory measures in Israel as follows:

Level One: Increasing Attention and Learning from Global Experience. Establishing joint social partners—regulators, working groups, and forums—to study the risks and benefits of AI implementation, particularly regarding inequality and effects on socioeconomic peripheries.

Level Two: Encouraging Experimentation with AI Regulation in the Workplace. Developing tools, best practices, and training for AI technology use in accordance with work laws; promoting collective agreements on technology integration in work processes.

Level Three: Fundamental Legislative, Doctrinal, and Strategic Reforms. Mandating employer disclosure to employees on the use of AI in decision-making, enshrining privacy rights and anti-discrimination provisions, and instituting mandatory bargaining over significant technological changes in the workplace.

Level Four: Investment in Infrastructure and Programs for Integrating Workers from Socioeconomic Peripheries. Developing technological and human infrastructure with an emphasis on socioeconomic peripheries, identifying paths and encouraging the use of AI to reduce social disparities, and strengthening the involvement of social partners.

Conclusion

Israel has paid limited political and regulatory attention to the effects of AI on the labor market. However, AI is integrating into the labor market, which warrants political and public attention.

Alongside the significant risks associated with AI adoption, the integration of these systems into Israel’s labor market holds potential for economic growth, reducing inequality, and improving working conditions.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems are integrated into workplaces and the labor market in a variety of still–developing ways. Employers use AI systems in employee screening and recruitment processes, in monitoring work performance, for scheduling shifts and determining compensation, in routine management of employee relations, and more. In addition, AI systems influence the workplace itself by transforming labor processes in production, with clients and suppliers, research and development, and management.

The use of AI systems and concerns over accelerated technological change have generated a great deal of discourse about the regulation of these systems and the roles of employees, unions, employers, and regulators (White House, 2022; Satariano, 2023). Alongside substantial investment, development, and implementation of AI tools in workplaces, we see academics, regulators, civil society organizations, and political actors worldwide engaged in identifying the risks and the benefits of AI use (Calo, 2017; Scherer, 2016). A broad swath of literature—academic, professional, and popular—is being published on the interface between AI and public policy and regulation (Turner, 2018). The role of labor unions and employers’ organizations, and forms of coordination and synchronization based on social partnership relations concerning AI use in the workplace, is becoming a new and emerging field of research and early experimentation (De Stefano and Doellgast, 2023).

Researchers across the globe differ in their worldviews regarding the likely impacts of AI systems qua technological change on the labor market; some are optimistic, others pessimistic. Techno-pessimists (researchers and policy makers who are more concerned about the negative effects of technology) fear mass unemployment resulting from the replacement of millions of workers and deepening inequality. Techno-optimists predict that significant adoption of AI tools will lead to substantial increases in GDP (Goldman Sachs, 2023) or significant economic growth without negative implications for working conditions (The Economist, 2023).

Alongside these technology-focused perspectives, a growing research consensus has emerged that the impacts of AI adoption on the labor market, like most other technological advancements, are not predetermined by the type of technology. It is impossible to predict, per this consensus, the general trajectory of AI’s social effect without considering the strategic and institutional environment in which AI will be developed and implemented. Leading scholars examining labor markets, inequality, and AI argue that, as the effects of AI adoption depend on labor market institutions and actors, it is possible to shape those market institutions in ways that ensure AI adoption produces both economic and social benefits.

Even within this significant body of literature, researchers differ in emphasizing the risks or benefits of AI. Daron Acemoğlu, an MIT economist and Nobel Laureate, argues that the impact of AI integration in the workplace depends on employers’ adoption strategies, which themselves depend on market institutions and on the strategies of companies producing AI products. According to Acemoğlu, whether consciously or not, employers face a strategic crossroads: whether to adopt technologies that replace workers (e.g., replacing workers performing certain tasks with technology doing the same tasks) or to adopt technologies that augment the added value of existing workers (e.g., integrating technology into current employees’ work). Acemoğlu contends that, at present, employers and technology producers tend to favor replacement strategies. He warns that continued mass adoption of replacement technologies will lead to significant increases in unemployment and a marked decline in workers’ wages relative to labor productivity (Acemoğlu and Johnson, 2023).

Orly Lobel, a legal scholar at the University of San Diego, describes in her book The Equality Machine how AI-based technologies can positively transform both the world of work and society as a whole. Lobel presents AI as a technology capable of closing wage and working condition gaps between different groups of workers, such as income disparities between men and women (Lobel, 2024; Lobel, 2022). According to Lobel, AI technologies can help close labor market gaps by exposing instances of discrimination and providing tools to prevent them. She explains how data collection and processing can reveal discriminatory processes that would otherwise remain hidden without digital management and the capacity to process large amounts of data. Moreover, Lobel highlights that existing labor market discrimination is often rooted in human decision-making processes, which are biased—both consciously and unconsciously—against certain worker groups. She describes the potential integration of AI systems alongside human decision-making processes, whereby AI serves to improve human decisions and remove discriminatory factors.

That said, Lobel and Acemoğlu share three foundational views on AI integration in workplaces.

First, they agree that the direction AI takes in the labor market depends on institutions, regulation, and technology adoption strategies. AI does not autonomously plan, develop, package, sell, implement, or correct itself. Governments, employers, investors, providers, and workers shape and choose how the technology is adopted.

Second, both recognize significant equality potential in AI integration strategies. Acemoğlu emphasizes vertical social equality—how the gains from growth are divided between workers, employers, and investors; Lobel emphasizes horizontal equality—closing gaps between different worker groups (Mundlak, 2011). Both scholars agree that, with the right institutions, strategies, and approaches, AI adoption has tremendous positive equality potential for labor markets and workplaces. Lobel summarizes this approach by describing AI as a newly discovered natural resource—akin to oil or gas—with no predetermined purpose or outcome independent of society’s choices and strategies regarding its use.

Third, both advocate for adopting proactive technology policy: a policy committed to using technological development as a tool for achieving social goals, such as reducing inequality and promoting economic growth. In their view, without a technology policy, regulators and policy makers leave the direction of technology development and adoption to investors, manufacturers, developers, and employers—who may pursue paths that fail to generate positive social change.

In contrast to Lobel and Acemoğlu, however, much of the regulatory and academic discourse surrounding new technologies in the labor market focuses on risk minimization rather than benefit maximization. For example, Brishen Rogers of Georgetown University describes AI adoption in the workplace as a systematic deployment of tools that suppress workers’ voice and power (Rogers, 2023). Rogers is particularly concerned that employers can now transform collective processes (such as union formation) into individualized ones by transforming traditional workplaces into digital platforms or by exerting complete control over organizational information flows, micro-decisions, and work processes. From Rogers’ perspective, surveillance, monitoring, and filtering of communication among workers, both inside and outside the workplace, heighten employer control over workers’ ability to congeal into a distinct interest groups and to fight for a share of workplace profits.

Similarly, Ifeoma Ajunwa, a law and technology scholar at Emory University School of Law, describes in her book The Quantified Worker a growing trend of monitoring and controlling employees through new AI technologies. According to Ajunwa, AI adoption allows employers to collect and analyze significant volumes of data on individual employees and groups, thereby expanding employer monitoring and control capabilities (Ajunwa, 2023). Ajunwa is especially concerned with the intrusion of surveillance tools into employees’ own bodies, now harvested for biometric data and the erosion of physical privacy at work. For example, requiring employees to wear devices that monitor blood pressure, heart rate, breathing, and exertion—and linking these data to specific metrics such as location and pace—provides employers with direct access to workers’ biological information.

In their book Your Boss Is an Algorithm, Valerio De Stefano and Antonio Aloisi present a wide array of risks arising from the adoption of new technologies, including AI, alongside potential means for institutionalizing and regulating AI use (Aloisi and De Stefano, 2022). They warn that AI adoption could dismantle national welfare frameworks, eliminate workplace privacy rights, render unions irrelevant both in the workplace and in Western democracies, weaken workers’ bargaining power to the point at which vulnerable workers are excluded from social and political participation, and more. Alongside their extensive mapping of risks, De Stefano and Aloisi offer a broad range of policy solutions and regulatory proposals for updating labor market legislation and regulation. Their regulatory approach can be summarized as “Yes We Can”—meaning that it is possible to build regulatory capacities that proactively address both known and as-yet-unknown challenges.

In summary, much of the research and writing on AI integration in the workplace focuses on identifying and minimizing risks. Policy solutions proposed and implemented worldwide also center primarily on mitigating anticipated risks. However, this approach is partial, as it does not aim to optimize AI’s advantages and opportunities.

A. Risks in the Development and Implementation of AI Tools in the Labor Market

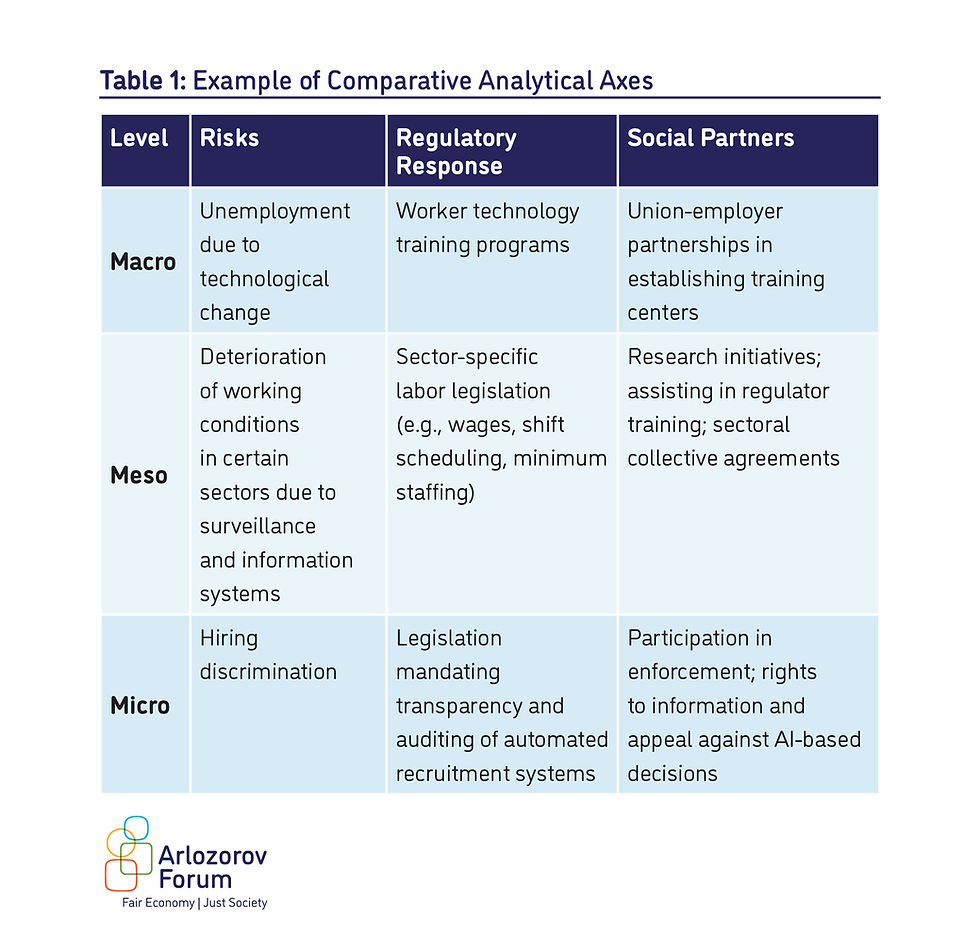

This chapter reviews the main risks identified in the research literature concerning the development and implementation of AI tools in workplaces and the labor market. For effective categorization of risks and related policy efforts, we divide the types of risks and corresponding regulatory and social responses into three levels:

Macro (national level): This level includes risks that pertain to the labor market as a whole or to systems parallel to the labor market (such as the political system, education system, and media) that may affect it.

Meso (sectoral or occupational level): This level includes risks that pertain to specific groups, occupations, and population sectors.

Micro (individual level – employees and employers): This level includes risks that pertain to the rights of individual workers and specific employers.

Macro-Level Risks

Mass Unemployment Due to Automation:

Like other technological shifts, AI tools may replace workers in performing tasks, potentially rendering large numbers of workers redundant across the labor market. The ability to substitute workers with AI may lead employers to reduce both direct and indirect employment. Unemployment risks caused by automation may simultaneously affect multiple sectors and professions, potentially resulting in a significant rise in the general unemployment rate (Estlund, 2018; Acemoğlu and Restrepo, 2019).

Increase in Horizontal Economic Inequality (Between Workers):

As productivity increases from AI integration, there is concern over an unequal distribution of gains among different groups of workers. For example, AI tools may be deployed in ways that replace workers performing physical tasks or those requiring only basic AI-related skills. This concern is based on forecasts suggesting that employers will tend to combine highly skilled, highly paid workers with AI tools while using AI to replace lower-skilled workers. Thus, the way AI systems are integrated may exacerbate economic disparities between central and peripheral labor markets.

Increase in Vertical Economic Inequality (Between Workers and Employers):Another type of inequality identified in the literature concerns growing income disparities between workers and employers. Productivity gains resulting from AI integration may be captured entirely, or primarily, by employers, leaving workers without corresponding wage increases. As labor productivity rises without wage growth, employers’ share of national income grows accordingly.

Employer bargaining power with workers may also increase due to reduced replacement costs, enhanced monitoring, and more effective control mechanisms (Rogers, 2023), further aggravating income distribution between employers and employees.

Weakening of Institutional Structures to Attract AI Development and Implementation: Researchers have expressed concern that labor market institutions may be weakened to attract capital or facilitate AI implementation. Existing work laws—such as worker classification rules, working hours legislation, and others—are often portrayed as outdated or ineffective relative to new technologies. The most extreme argument claims that all regulatory institutions are obsolete and that enforcing current legislation would inevitably lead to negative outcomes for emerging technologies. For example, applying working hour laws to platform-based work could limit worker flexibility regarding when and where they work (Aloisi and De Stefano, 2022).

Minimal or lacking Implementation of AI:

Alongside concerns about certain modes of AI deployment is also a risk of insufficient or lacking AI implementation in workplaces. Countries that fail to promote AI adoption, or actively slow its integration into labor markets, may lose competitiveness against nations where AI adoption enhances competitiveness. Insufficient use of AI may result in unfulfilled profitability potential and missed opportunities for addressing social disparities (Lobel, 2022).

Political Risks:

Beyond labor market economic risks are concerns over the acceleration of misinformation and disinformation, which may significantly undermine democratic states’ ability to function. Distorted information could influence democratic elections and decision-making processes by professional, governmental, or judicial actors.

Meso-Level Risks

Unemployment in Specific Sectors, Occupations, or Population Groups:

In addition to mass unemployment concerns, certain sectors—such as health care, maintenance, education, financial services, and human resource management—face heightened unemployment risks due to AI. Some population groups may also be disproportionately affected due to limited access to technological or language (e.g., English) skills or because of social stigmas about integrating specific groups (e.g., older workers, ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Arab citizens) into technology sectors. Unemployment in particular sectors may result from the sensitivity of certain professions to technological change, technology-driven competition, management strategies, or shareholder pressures in specific industries.

Decline in Labor Union Effectiveness:

Labor unions may be weakened by AI use as a result of unemployment in highly unionized sectors (e.g., public transportation), organizational changes that hinder membership recruitment and collective bargaining (e.g., fragmentation through subcontracting or the hiring of independent contractors), the ability to operate without physical workplaces, or the centralization of employment decisions via algorithmic tools, which makes it more difficult for unions to negotiate work conditions. Technological illiteracy among union organizers and professionals may also contribute to the weakening of labor unions.

Data Security Risks:

The rise of advanced information systems, including AI, and the expansion of workplace surveillance, combined with significant advancements in AI-based hacking tools, increases the risk of large-scale data breaches involving employees and clients along with ransomware attacks targeting workplaces or even individual employees. The broader and more detailed the data employers collect on their workers, the greater the privacy risks in the event of cyberattacks on employer databases.

Overreliance on AI Tools and Loss of Organizational Expertise:

AI tools integration may result in decision-making processes becoming concentrated within algorithms controlled by engineers or internal/external software professionals rather than by local organizational experts. A lack of technological literacy and the inability to evaluate AI decision-making mechanisms may lead to excessive dependence on AI outputs, in effect outsourcing workplace decision-making to AI systems.

Weakening of the Public Sector:

Beyond general concerns over AI non-adoption is a particular concern about insufficient AI implementation in the public sector, given a historical pattern of partial or absent digital technology adoption. Failure to implement AI in the public sector may reduce its ability to address challenges such as labor law enforcement. Additionally, this may create a technological gap between the public and private sectors, weakening regulatory capacities and prompting skilled personnel to leave the public sector for the private sector.

Regulatory-Technology Mismatch:

Technological change may create a “policy drift” problem, wherein existing regulatory tools no longer match present realities (Galvin and Hacker, 2020; Racabi, 2022). In the context of workplace AI, legal uncertainty may arise regarding the allocation of liability under labor and equality law. For instance, if an employer makes a discriminatory decision based on AI outputs, it may be unclear who bears legal responsibility under antidiscrimination statutes (Vladeck, 2014; Solum, 1992). The absence of clear regulatory answers may generate legal uncertainty, with costs ultimately passed on to consumers and workers.

Micro-Level Risks

Workplace Discrimination:

A core concern regarding AI in the workplace is the replication of existing discrimination against women and minorities (disparate treatment claims) or the emergence of discriminatory outcomes through AI use (disparate impact claims) (Barocas and Selbst, 2016; Buolamwini and Gebru, 2018; Noble, 2018; Wachter-Boettcher, 2018). It is worth noting that the use of AI might also aid in reducing or sidestepping human biases currently integral to workplace decision making (Lobel, 2024).

Direct Discrimination:

Direct discrimination occurs when an AI system ranks workers or job applicants based on prohibited criteria (such as gender, ethnicity, or residence) or fails to account for legally mandated accommodations (e.g., workplace accessibility for employees with disabilities). A well-known example of direct discrimination involved Amazon’s hiring algorithm for software engineering roles, which downgraded women because the algorithm was trained on historical data that included very few women in relevant positions (Dastin, 2018).

Indirect Discrimination:

Indirect discrimination arises when AI systems disadvantage certain groups due to characteristics disproportionately present within those groups. For instance, AI systems may use multiple data sources—including social media data—for employee and candidate ranking. This may disadvantage groups less active on social media (e.g., older individuals) or non-native language speakers when AI systems rely on language-specific data (e.g., Hebrew). In such cases, social media presence—which correlates with protected demographic characteristics—affects workplace decisions regarding hiring and terms and conditions of employment.

Surveillance, Monitoring, and Privacy Violations:

Another concern involves violations of privacy. For example, employers may monitor maintenance workers throughout their shifts using combinations of smartwatches and cameras. Employers may also use biometric data collected outside of work hours (e.g., via smartwatches) to make decisions regarding scheduling, wages, or terminations (Hirsch, 2020; Kellogg, Valentine and Christin, 2020).

Transparency and Information Gaps:

AI-based hiring and personnel management introduce new problems of transparency and information asymmetry. First, workers may be unaware that AI systems are involved in decisions affecting them (e.g., hiring). Second, AI systems make decisions by processing numerous factors with complex interrelations, rendering the process opaque to workers—a phenomenon referred to in the literature as the “Black Box problem” (Barocas and Selbst, 2018; Coglianese and Lehr, 2019; Kroll et al., 2017). Although managerial decision-making processes have always been somewhat opaque, AI now allows employers or service providers to design decision-making systems in ways not possible via purely human actors. This increases information gaps between employers and employees and among applicants with differing levels of AI expertise.

Arbitrariness and Lack of Procedural Rights:

One consequence of transparency and information gaps involves procedural justice. When decisions are made in ways that are opaque even to formal decision-makers (e.g., employers, but also governments or judges), workers may be left without avenues for appeal or access to information about decisions affecting them. This can increase arbitrariness in the workplace and erode perceptions of procedural justice concerning employment decisions.

B. Comparative Review of AI Regulation

Around the world, political and legal institutions, commercial enterprises, and civil society organizations are actively engaged in learning and shaping AI regulation. Different countries formulate their AI policies based on internal and external political pressures, existing labor market institutions, current regulatory frameworks governing employee rights, the relations between social partners (labor unions and employer organizations), and each country’s position in the AI value and production chain as determined by political leadership and professional government officials.

In this chapter, we describe the regulatory approaches various countries have adopted and how these approaches aim to address specific risks arising from AI integration. It is important to note that some regulatory responses may generate risks of their own. For instance, to address shortages of technologically skilled workers, countries may open their labor markets to qualified immigrants (as in Germany) (Brown, 2024); however, doing so may increase inequality in the economy or in specific sectors and may weaken the power of labor unions.

In most examples, regulation remains under development, and rapid changes in regulatory frameworks may occur. At the end of each country-specific section, a table summarizes selected risks, benefits, and the role of social partners in AI regulation[1].

The mapping of risks, regulatory responses, and the role of social partners is presented along the macro, meso, and micro levels for each country.

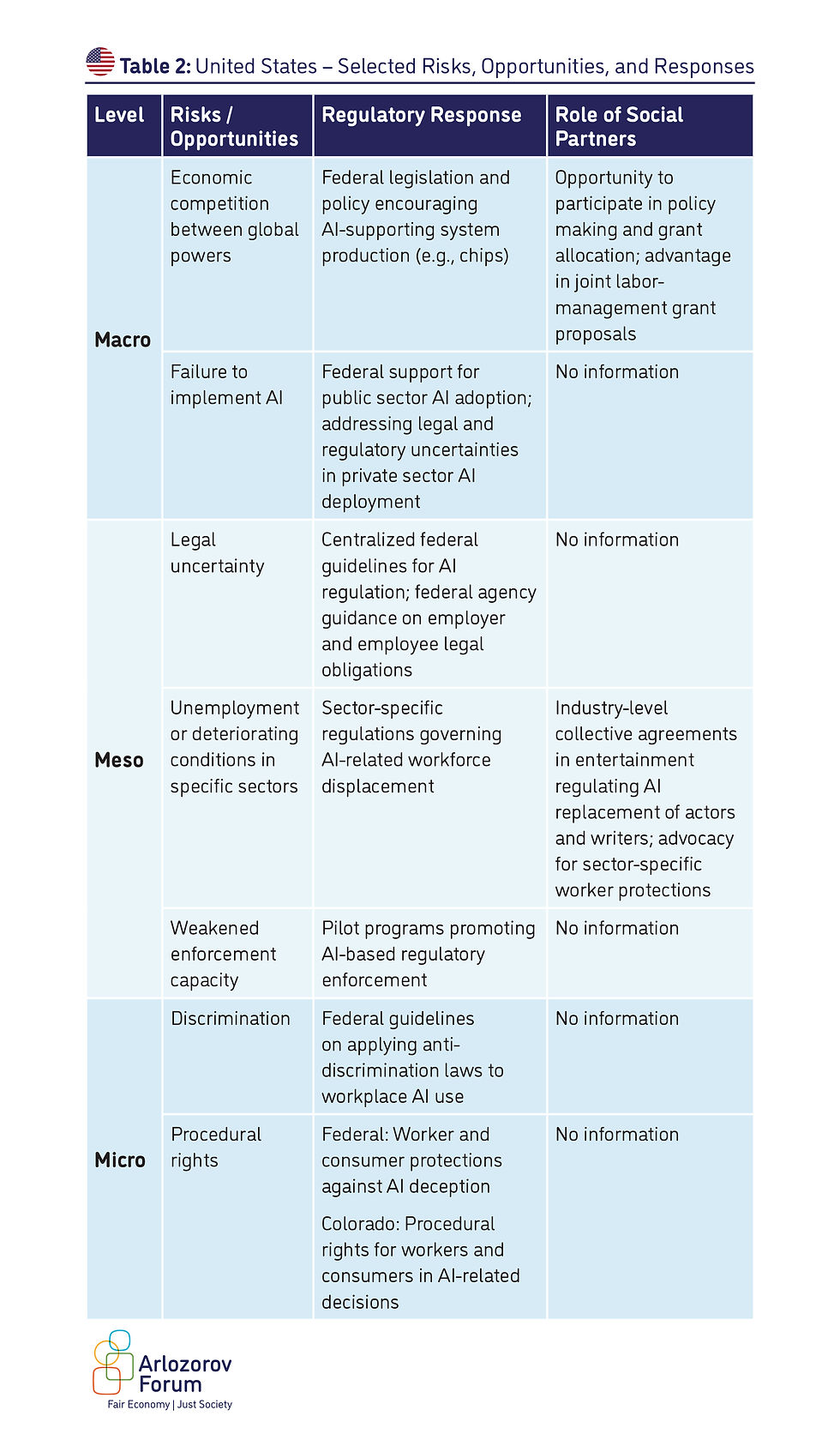

United States

The United States seeks to position itself as a global leader in AI development and the technological infrastructure on which AI systems operate (e.g., processors, cloud computing). Intensifying economic competition with China and Europe has led the U.S. government to adopt unconventional measures, including substantial investment in manufacturing infrastructure, public-private partnerships focused on production and scientific education, and the establishment of shared federal infrastructure for AI regulation.

The most significant legislation in this area is the CHIPS and Science Act, which establishes various subsidy mechanisms for research on AI’s impact on the labor market, primarily through large-scale subsidies for manufacturing infrastructure and hardware development. The implementation of the CHIPS and Science Act is in its early stages, but preliminary indications point to significant growth in U.S. hardware development and production investment. Part of this effort involves encouraging public-private partnerships between corporations, local governments, higher education institutions, and labor unions. These initiatives compete for federal grants to fund development-related infrastructure, including STEM education (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and adult education programs (Magor, 2024).

On the regulatory side, the federal government has issued a series of guidelines that, unusually for the decentralized U.S. regulatory system, set out core principles for AI regulation. Generally, these guidelines focus on two major risks: (1) insufficient market demand for AI products in the U.S. and (2) risks to minorities, consumers, and workers (e.g., discrimination, privacy violations). In response to the second risk, the government supports increasing AI market demand by reducing regulatory barriers for the private sector and promoting public sector technological development. The administration has also instructed all federal agencies to integrate AI into internal processes, such as enforcement and regulatory compliance monitoring.

Several agencies responsible for enforcing federal labor laws have issued guidelines on how existing labor legislation applies to AI systems in the workplace:

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC):

The EEOC is the federal agency responsible for enforcing equal employment opportunity laws (covering workers with disabilities, sex and race discrimination, and more). A central issue for the EEOC concerns employer and third-party liability for discriminatory outcomes resulting from AI use. The agency has issued guidance clarifying that employers using AI products for workplace decisions (e.g., candidate screening, wage setting, time tracking) are legally liable under equal employment law for discriminatory outcomes, even if the technology was purchased from third-party vendors (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2023). In legal proceedings involving AI-based hiring discrimination, the EEOC is also seeking to establish third-party vendors as legally responsible for discriminatory outcomes caused by their technologies.

Additionally, the EEOC has issued guidance warning employers about using AI systems for decision-making concerning employees with disabilities, emphasizing that such systems may overlook accommodations required under federal law (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2022).

National Labor Relations Board (NLRB):

The NLRB is the federal agency responsible for enforcing the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the primary statute governing collective labor relations in the private sector. The NLRB general counsel, who holds exclusive authority to prosecute NLRA violations, issued guidance stating that monitoring employees using AI-based technologies may violate prohibitions on interfering with organizing efforts (National Labor Relations Board, 2022). The underlying rationale is that AI technologies allow employers to process vast amounts of data non-transparently and that such surveillance may deter employees from organizing. The guidance imposes a duty on employers to ensure surveillance practices do not infringe on workers’ and unions’ rights protected under the NLRA.

Department of Labor (DOL):

The DOL enforces core federal labor protection statutes, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (governing working hours and overtime pay) and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (governing workplace safety and hygiene). The administration has tasked the DOL with developing guidance on how these laws apply to AI tools, but as of yet, the DOL has not issued such guidelines. However, the DOL has experimented with AI enforcement tools—for example, processing medical forms using AI and piloting safety inspections utilizing drones and AI-based software.

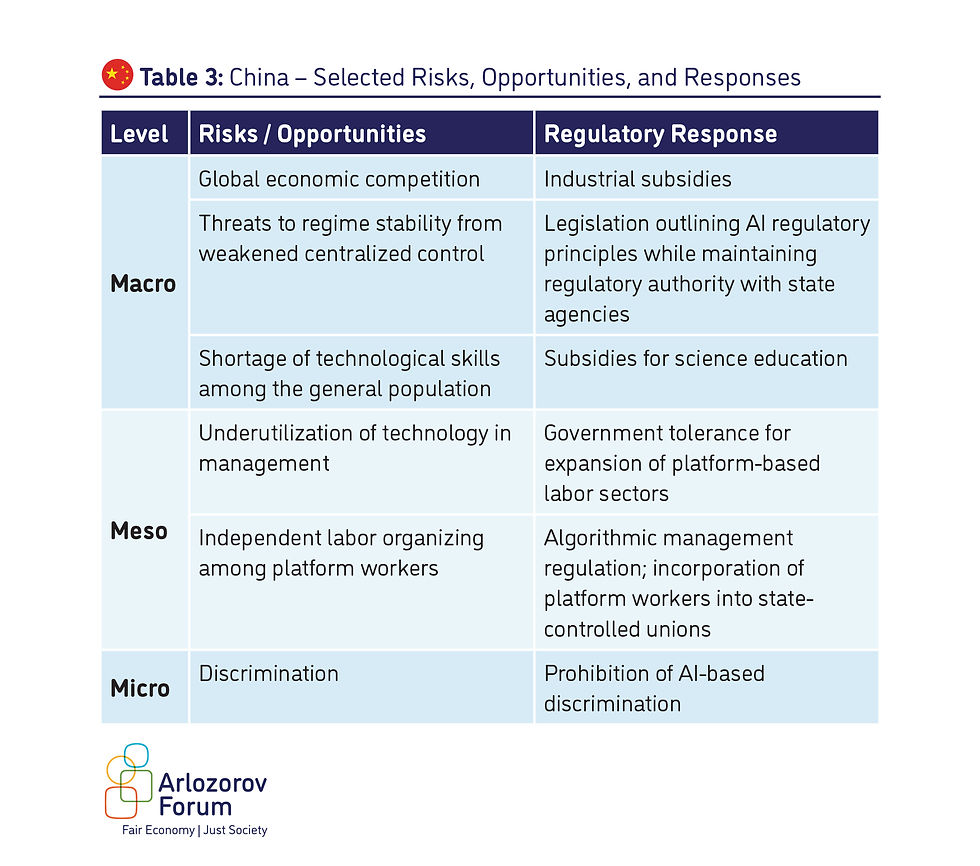

China

China is the United States’ primary global competitor in the development and deployment of AI and is among the countries with the most comprehensive AI regulation. As in the U.S., China’s AI regulation serves both domestic and international objectives, with the external focus directed at competition for global market share. In contrast to the U.S.—where regulatory authority is decentralized across federal and state levels—China’s regulatory authority stems from centralized party leadership, and domestic AI regulation primarily aims to preserve the legitimacy of centralized governance (Liu, Zhang and Sui, 2024).

As with the U.S., China’s AI development and implementation policies are openly declared. The central policy objective is to balance the advancement and use of advanced technologies with the need to maintain governmental stability. The practical implementation and enforcement of these policies fall to various administrative authorities[2].

China’s macro-level digital tools policy matured in the second decade of the 21st century alongside the rise of digital commerce giants such as Alibaba and TikTok. The current phase includes substantial subsidies for strengthening scientific education and digital literacy along with creating favorable regulatory conditions for local companies using AI in labor management, especially platform-based employers.

At the same time, the Chinese government has adopted measures restricting AI use in the workplace. For example, algorithmic decision-making at work must be reported to the authorities and disclosed to employees. Furthermore, the government has prohibited discrimination through AI and imposed management and oversight obligations on employers using AI. However, concerns remain that despite the appearance of strict employer obligations, enforcement may be lacking (Liu, Zhang, and Sui, 2024).

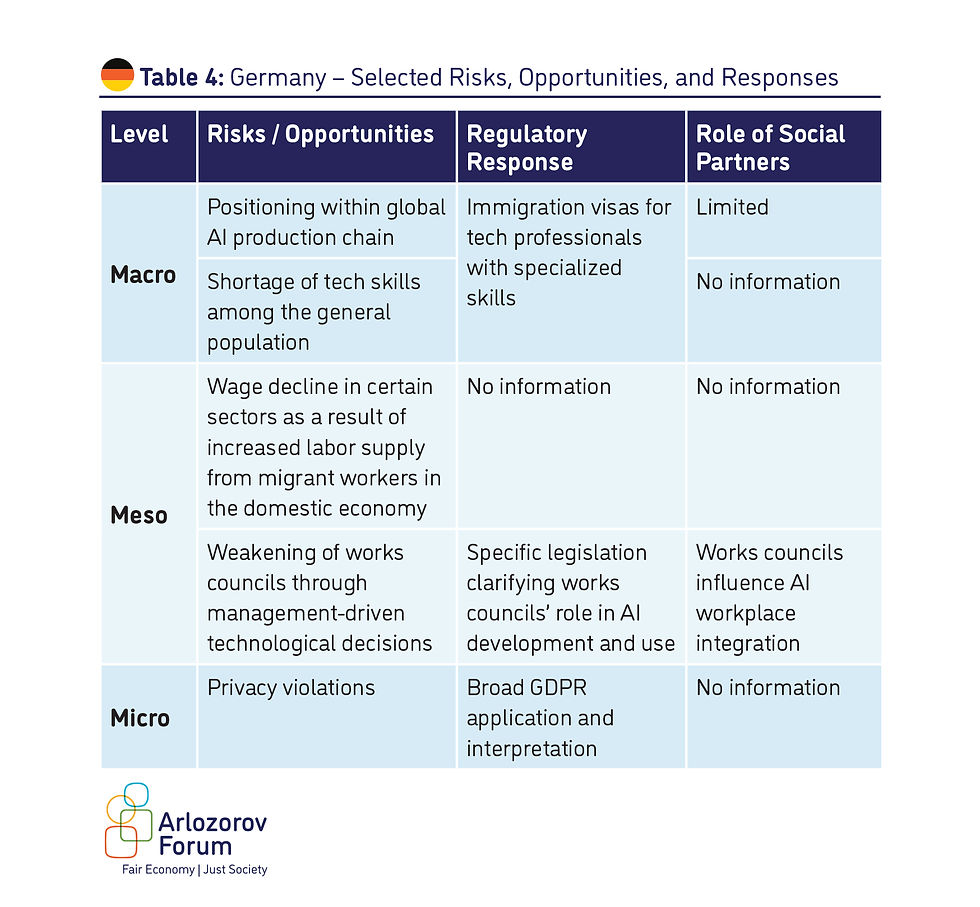

Germany

As with the U.S. and China, Germany is positioning its high-tech and manufacturing sectors to play a leading role in the global AI market, producing policy documents that integrate AI production strategies with domestic workplace AI regulation.

Germany faces a significant shortage of technologically skilled workers, prompting pressure for training programs and employer-driven advocacy for more lenient visa policies to attract skilled foreign workers. Because foreign labor in tech manufacturing often commands relatively lower wages, the literature raises concerns over how this development may worsen inequality and limit migrant workers’ integration into workplaces and sectors with lower union coverage (Özkiziltan, 2024).

Unlike the U.S.—and more similar to China—Germany and the broader European Union already have a regulatory framework protecting privacy that limits certain forms of digital monitoring and control. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the most advanced privacy protection standard for both consumers and workers, and Germany has issued additional regulatory guidance specifically applying GDPR principles to consumers and workers (Lorenz and Gabel, 2024). For example, employers are required to define the purpose of AI use, ensure transparency, and develop monitoring tools to assess AI’s workplace impact. While the application of privacy law to AI in workplaces remains under development, GDPR and European labor law are expected to create relatively strict privacy standards for workers.

Additionally, Germany’s Works Council institution was reinforced in 2021 by the Works Council Modernization Act, which mandates employer disclosure of AI usage to works councils and encourages their involvement in AI-assisted recruitment processes. The law requires employers to fund technical experts to assist works councils in fully understanding AI systems the employer deploys (Riso, 2020). This regulatory innovation strengthens works councils as a foundation for workplace worker representation even as AI is introduced into work processes (Boord, 2023).

Scandinavian Countries

The Scandinavian countries (Norway, Denmark, and Sweden) are characterized by comprehensive welfare policies and a strong influence of social partners over labor markets and working conditions. These countries also possess relatively advanced technological infrastructure in both public and private sectors. In line with their responses to other technological challenges—such as platform economy integration—AI regulation emphasizes the strengthening of joint institutions involving government, employers, and labor unions under broad regulatory frameworks that protect rights such as privacy, while defending Scandinavian model autonomy against European Union pressures (Ilsøe et al., 2024).

In all Scandinavian countries, labor and employer organizations participate in committees studying and documenting AI’s labor market effects and serve as significant platforms for policy making. For example, Denmark’s government established joint labor-employer committees to address labor market policy in response to digitalization, including AI-related issues. Across Scandinavia, labor unions seek to address AI using existing labor legislation and collective bargaining structures, including general clauses in collective agreements protecting workers’ rights without requiring AI-specific regulation (Ilsøe et al., 2024).

Several collective agreements in Scandinavia already govern workplaces reliant on digital technology (e.g., platform companies), often containing provisions protecting worker rights in algorithmic management and data privacy (Jesnes, Ilsøe and Hotvedt, 2019). However, uncertainty remains over the effective enforcement of such provisions given rapid technological changes and evolving algorithms.

South Korea

South Korea (hereafter, Korea) has a significant manufacturing sector. In 2023, approximately 25.6% of its GDP was based on advanced technology manufacturing, which is a core element of the Korean economy’s competitiveness (Kim and No, 2024; Statista, n.d.). The Korean government promotes AI-driven development and production through three regulatory channels: infrastructure, STEM education, and investment in the technological transformation of small and medium-sized enterprises. Over the past 30 years, Korea has invested heavily in internet infrastructure, improving both broadband access and high-speed connectivity. Korea also directly funds technological research and education in partnership with various commercial enterprises and academic institutions.

AI regulation in the workplace in Korea relies on the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA), which constitutes a weaker version of GDPR protections, offering fewer safeguards against unfair digital data usage. In the coming years, PIPA is expected to be amended to impose notification requirements on companies using AI and obligations to explain AI-based decisions to users.

Labor unions and employer organizations participate in a government-appointed committee studying AI’s impact on the labor market and are expected to submit regulatory recommendations. In addition, Korean labor unions are investing efforts to organize tech and manufacturing workers involved in AI, along with platform economy workers whose working conditions are shaped by algorithms and AI. For example, the Rider Union, representing food delivery couriers, demands transparency in algorithmic management and platform surveillance of workers. Traditional manufacturing unions, such as those at Kia, are also negotiating the integration of AI-driven automation into production processes (Kim and No, 2024).

South Africa

In South Africa, alongside efforts to develop a domestic high-tech industry and concerns about worker privacy rights, two AI-related labor risks exist that are not present in the more developed countries surveyed above. The first risk concerns workers at the margins of the labor market who perform tasks within the AI production chain. The second is the fear that authoritarian regimes will exploit data collected on workers and labor unions engaged in conflict with employers and political authorities (Bischoff, Kamoche and Wood, 2024).

In South Africa, as well as in Kenya, researchers have documented the growth of a "ghost work" sector (Gray and Siddharth, 2019) where workers clean data sets and train AI algorithms. Labor markets in Kenya and South Africa—where many workers, including migrants from other African countries, have limited bargaining power—allow employers to establish "ghost worker farms" offering data cleaning and moderation services. Alongside the establishment of government committees and employer organizations advocating for ethical AI development in the workplace, workers’ weak bargaining power creates pressure on the government to maintain relatively lenient regulatory conditions for AI deployment.

C. Israel: Current Situation and Future Proposals

Israel lags behind many countries in preparing for AI integration in the workplace (Orbach, 2024). Unlike many countries worldwide, state-level and social partner preparations for AI adoption in Israel remain limited. In contrast to the U.S., the European Union, and the East Asian and African countries surveyed above, Israel has no national policy aimed at integration into the global AI value and production chain. However, government programs do exist to promote AI-related research, development, and public sector use (Israel Innovation Authority, 2024), and Israel has signed international declarations on ethical government AI use.

The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Innovation have issued a policy, ethics, and regulation principles document addressing broad questions, such as the applicability of existing law and ethical considerations for AI development and deployment (Ministry of Justice, 2023). The document favors sector-specific (rather than general) AI regulation, focusing on industries such as banking, tourism, and security. It also encourages regulatory experimentation and AI sandbox programs that allow entrepreneurs to develop technologies within relaxed regulatory environments. The document broadly addresses contracts, torts, privacy, and consumer protection, but aside from general reference to discrimination, it does not address labor market issues.

A small number of studies have attempted to estimate the exposure of specific occupations and sectors in Israel to AI’s impact (Debawy et al., 2024), but these studies assume static regulatory policy and unchanged employer-union strategies, limiting their relevance.

Israel also has limited experience in developing labor market regulation for new technologies compared with the countries surveyed. Unlike these countries, Israel has not addressed platform-based work through regulation or general labor policy. Unions have also struggled to gain a foothold among platform companies. Instead—and unlike other countries—Israel’s regulatory approach to platform work has relied on market entry restrictions (e.g., banning Uber) or labor court rulings applying general legal doctrines and basic labor protections (e.g., Wolt). However, the absence of regulation does not eliminate the problem. The lack of experience regulating platform work creates a significant gap between Israel and other countries that have learned from hands-on regulatory experience with technology-mediated work and are now applying those lessons to new regulatory initiatives.

That said, Israel possesses several institutional advantages that could support an effective AI response. These include relatively broad union coverage, flexibility in the content and scope of collective agreements, and a tradition of significant social partner cooperation involving employers, workers, and the government. Another advantage is Israel’s dedicated labor court system, which has developed experience addressing technological changes in the labor market–such as applying general privacy principles to computers, email, and biometric monitoring in the workplace.

Additionally, Israel has a broad framework of labor protection legislation, including detailed wage arrangements, extensive equal opportunity laws, privacy protections, and social security. Workplace privacy is also a recognized and active regulatory field (Privacy Protection Authority, 2017). The Ministry of Justice’s sectoral regulatory approach to AI aligns with Israel’s sector-based labor regulatory tools, offering a built-in role for social partners in developing regulation.

Nevertheless, Israel’s institutions have only partially succeeded in addressing labor market changes. The expansion of fragmented employment arrangements, particularly through independent contracting (freelancers), represents a growing structural problem. Labor market sectorization—between ultra-orthodox, Arab, and secular populations and between center and periphery—remains an unresolved challenge. Additionally, unequal infrastructure investment across geographic and demographic sectors presents a major obstacle for developing effective responses to both existing and future labor market challenges. The lack of public attention to these structural labor market problems due to various reasons poses a serious challenge to any solution requiring significant political mobilization.

In light of Israel’s labor market structure and existing challenges, we propose four regulatory levels for Israel. Each level builds upon the previous one and requires progressively greater political investment and joint mobilization by regulators and social partners.

Level One: Increasing Attention and Learning from Global Experience

Objective

To date, most attention regarding AI regulation has not focused on the impact of AI development and implementation on labor markets and workplaces. Because AI in the workplace has not yet become a public or regulatory priority, the perspectives of social partners—and particularly of workers—on AI development and implementation are largely absent. Therefore, the goal of the first level is to dedicate regulatory and strategic attention to the most significant macro- and micro-level risks of AI integration in the labor market, with particular focus on inequality and labor market peripheries.

Role of Regulators and Social Partners

Establish a joint working group of workers, employers, and regulators to examine existing regulatory and contractual mechanisms (e.g., collective agreements) that address AI, to map selected risks, and to propose possible solutions.

Establish internal committees within social partners (labor unions, employer organizations, and sometimes the government) to explore AI integration into state systems and social partner institutions. For example, create dedicated employer and union forums to study real-world AI applications in labor markets and develop corresponding strategic responses.

Role of Labor Courts

Form a specialized study group of labor court judges to examine AI’s impact on labor markets and workplaces and study the roles of social partners and regulators in other jurisdictions.

Level Two: Encouraging Experimentation with AI Regulation in the Workplace

Objective

Israel has limited experience regulating new workplace technologies. This level aims to encourage experimentation with AI regulation in the labor market and to foster agreements between social partners regarding AI implementation and development. A key component at this stage is informing workers and employers about the existence of AI systems and the applicability of existing laws to their operation. This includes encouraging collective agreements that regulate AI integration at the workplace level.

Role of Regulators

Develop technical guides and conduct training sessions and workshops for employers, workers, and worker representatives on applying labor protections in AI environments.

Establish a mechanism for collecting regulatory questions from workers and employers related to AI integration and develop an advanced ruling mechanism to provide official regulatory guidance.

Role of Social Partners

Create a repository of best practices for drafting collective agreement clauses or enforcing existing provisions relating to AI.

Engage in bargaining over AI’s presence and impact in the workplace, incorporating necessary provisions into enterprise or sectoral collective agreements.

Promote training programs to enhance technological literacy for both workers and employers, including identifying at-risk jobs and developing retraining or knowledge-updating programs for workers and managers.

Level Three: Basic Legislative, Doctrinal, and Strategic Reforms

Objective

To establish regulatory alignment regarding the application of existing laws to AI systems and to affirm the importance of AI regulation in the labor market.

Role of Regulators

Identify incentives for social partners to negotiate AI adoption and workplace impacts. For example, condition the extension of general collective agreements on negotiation over AI adoption.

Condition Israel Innovation Authority grants on the development of ethical codes for AI development and use.

Role of the Legislature

Amend the Notice to Employee Law to require workers and job applicants to be informed when AI is used in hiring or screening decisions.

Amend the Equal Employment Opportunities Law to impose joint liability for discrimination arising from AI use on both employers and third-party vendors (software providers, candidate screening platforms).

Role of Labor Courts

Expand the duty of good faith in collective bargaining to include mandatory bargaining over significant technological changes.

Clarify that mandatory pre-termination hearings must be conducted by a human manager, not via AI systems.

Level Four: Investment in Infrastructure and Programs to Integrate Workers from Socioeconomic Peripheries

Objective

Beyond applying existing law to AI systems and leveraging the role of social partners, AI holds significant positive potential for economic development and reducing inequality. This level seeks to realize AI’s positive potential.

Role of Regulators

Develop programs promoting both technological and human infrastructure, with special attention to socioeconomic peripheries and the public sector. Emphasize cross-sectoral collaboration between social partners and public institutions.

Adopt legislation that broadly defines AI development and implementation in the workplace and establishes comprehensive individual and collective worker rights.

Individual rights: Notification rights, privacy protections, broad anti-discrimination provisions, hearing requirements, and appeal rights for AI-based decisions.

Collective rights: Obligations to bargain over AI integration, information and consultation rights, and worker voice and representation in AI development and implementation.

Encourage pilot programs that leverage AI to reduce employment and working condition disparities between labor market sectors.

Role of Social Partners

Develop labor market entry and retraining programs for workers currently outside the labor force.

Promote sector-specific solutions through industry-wide collective agreements.

Develop strategies for addressing fragmented employment and vulnerable workers at the bottom of AI’s global value chain (“ghost workers”).

Conclusion

The integration of AI systems into labor markets and workplaces is already a reality; political and public inattention does not change this fact.

In this paper, we analyzed the risks and opportunities associated with AI integration into labor markets and workplaces, followed by a comparative review of regulatory strategies and social partner involvement in various countries. We found that many nations pursue proactive strategies of integrating public labor market goals into AI’s development, production, and deployment value chains. The existence of such macro strategies helps guide national AI regulation. We also identified diverse pathways for integrating into the AI value chain: Even countries not aiming to control the top of AI production (such as the U.S. and China) adopt active regulatory policies to prepare core sectors of their economies for different stages of AI development, deployment, and integration.

We then described the current situation in Israel, where public and regulatory attention to AI’s labor market impact remains limited. In the absence of regulation and social partner coordination, the default forum for regulating AI’s workplace effects is the labor courts. However, we found no examples globally where national responses to AI workplace integration rely exclusively on the judiciary.

In the final section, we proposed four regulatory policy levels for addressing AI integration into Israel’s labor market. These recommendations seek to draw regulatory, political, and professional attention to AI-related labor market risks and opportunities; create legal clarity; and promote discussion and policy proposals for managing AI’s profound implications in the workplace.

Following these recommendations can help social partners respond to both the risks and opportunities the most significant technological change of our time has presented.

[1] The information regarding some of the countries is limited due to language limitations and research availability.

[2] An English translation of the legislation is available here: https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/generative-ai-interim/

תגובות